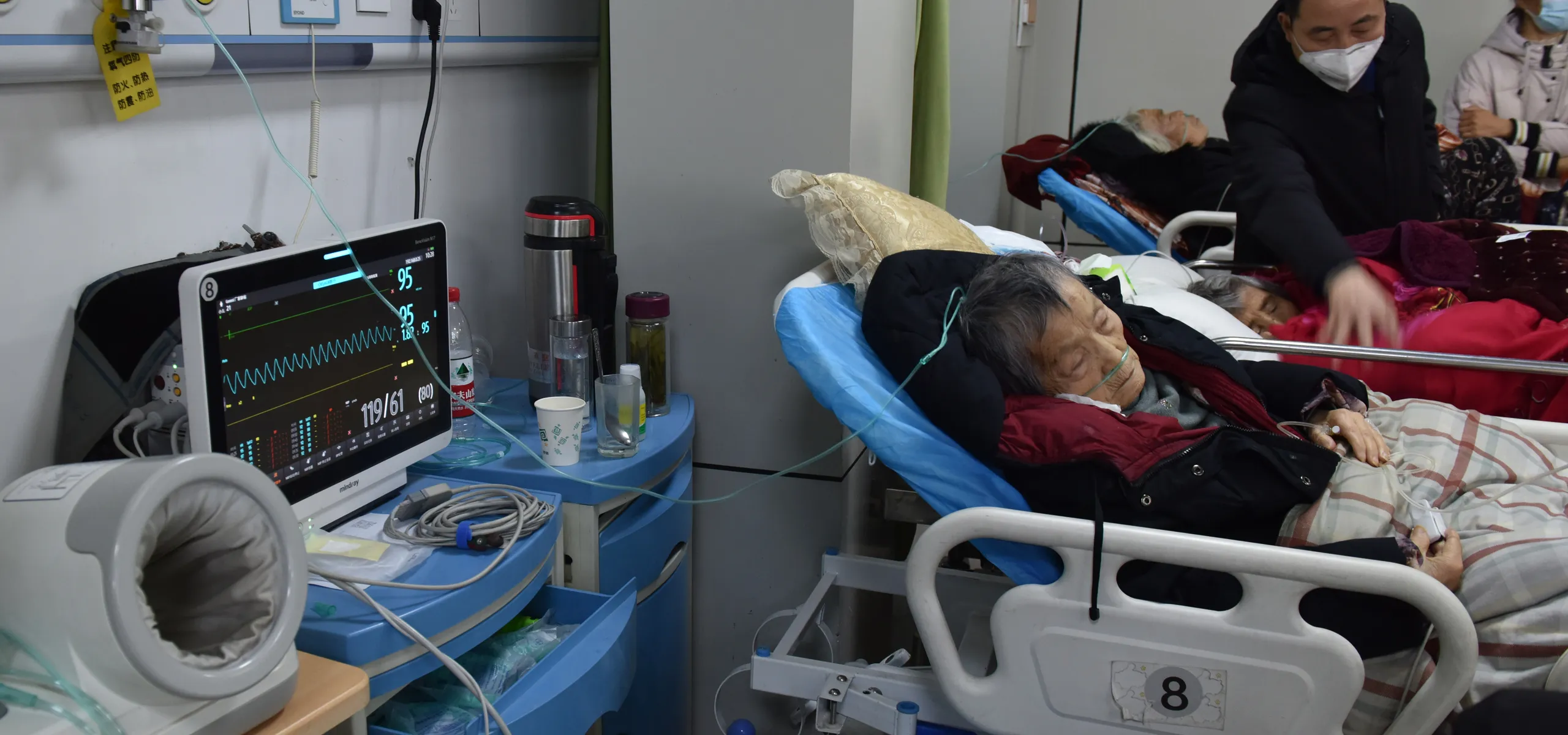

As the pandemic ravaged China in late 2022, a family struggles with the decision to send a dying elder to overcrowded hospitals

1/8

In early December last year, following China’s rollback of its strict pandemic controls, both my mother’s sisters—my eldest and youngest aunts—were infected with the virus in close succession. There was a third person living under the same roof as them—my maternal grandmother, or Waipo, a dainty, elderly lady who was already 95 years old at the time and barely weighed 70 pounds. Soon enough, she also came down with a persistent fever and cough.

Waipo’s frail health predated her catching Covid-19. She had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease two decades ago, at the age of 73, and it had ravaged all memories of her own self, and of her relatives. For a while, she could still walk; she could easily go on for some two or three kilometers before anyone could stop her. However, that too came to an end five years ago, when she broke her left leg and never quite healed from her injury. Thus, the confines of her world were reduced to those of her narrow bed and her wheelchair. There had been a gradual deterioration of her leg muscles. Her legs themselves were now just bones covered by a thin, rough layer of skin resembling sackcloth. She wasn’t really able to keep her back straight, whether she was lying down or sitting up, so walking was out of the question.

Waipo had one son and three daughters. However, Uncle suffered from lifelong disabilities derived from hearing issues since his early childhood. He relied on sign language for daily communication, and though he did a great deal at the household, he spoke very little. He left all relevant decision-making to his wife and sisters and kept himself busy in the family home, including watching over Waipo. Once in a while, Mom and her sisters came over for a few days at a time to give Uncle and his wife a brief respite from their routine, so that they could go for a walk and rest. This went on until early last year, when Uncle was diagnosed with advanced bowel cancer. His illness and his own surgery and chemotherapy kept his family busy. Eventually, it was decided that Waipo would move into the suburbs with my aunts. My mom also lived in the area.

The situation was not easy on Waipo’s three daughters. All three were already retired and had their own lives to live. My eldest aunt hopped on a bus every afternoon to go pick up her own granddaughter from school, more than 10 kilometers away. Mom was a breast cancer survivor herself and still reeling from her own round of post-surgery chemotherapy three years ago. In fact, Dad was in charge of cooking in our household, because it took little more than merely lifting an iron pot to sap my mother’s strength. Eventually, my youngest aunt stepped up to take care of Waipo. After all, she had no grandchildren to take care of, seeing as her own daughter was single and busy with her government job in the city. Auntie’s husband had also reached retirement age, and they were both in good health, with plenty of free time.

Not only was my youngest aunt the best candidate to take on Waipo’s care; she volunteered before her sisters could even bring it up. She tidied up their study room, where she set up a brand-new nursing bed, the kind of model that can automatically turn you over and sit you up, as well as Waipo’s wheelchair and stacks of diapers, changing clothes, bedding, and more. All this she prepared before Waipo’s arrival. Some may regard caring for the elderly as a burden and a drag, but Auntie had nothing but a joyful, warm welcome for Waipo when she finally did move in.

—

However, Auntie’s many hurdles also began before Waipo fell sick with Covid-19. Her father-in-law was in critical condition with the virus, so her husband had to go take care of him. This left Auntie alone with Waipo, other than some occasional support from my eldest aunt and myself, in lieu of Mom, whenever my work would let me.

On these occasions, I would stay at Auntie’s house, feeding Waipo a light fruit supper before we plopped together in front of the TV to watch the music channel—her favorite. Once, I asked my aunt whether she ever felt caged at home in her new capacity as a caretaker. Was she bored now that Waipo’s care kept her away from her past routine of painting and guzheng lessons? But Auntie replied: “No, not at all.”

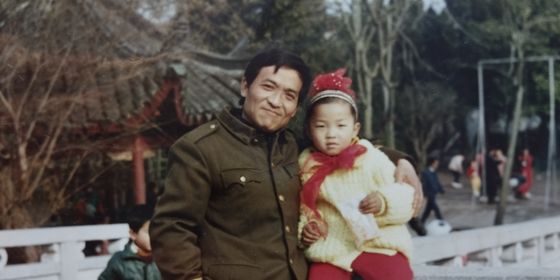

She followed her words with some revelations of her memories watching over her father’s deathbed in the ICU—my grandfather, Waigong.

I was still in college at that time. Auntie had been tasked with taking care of Waigong that day, but he just stared at her. Auntie felt something was off, so she got her face close to Waigong’s and whispered into his ear, “Dad, is something the matter?” However, at this point Waigong had already been intubated, so he couldn’t speak. He could only stare at Auntie. It finally dawned on her then, Auntie told me. She leaned in again close to her father’s ear and said, “You want me to take care of the family, right, Dad?” Waigong nodded vigorously. My aunt was taken aback momentarily, but then she immediately cracked a smile and reassured the ailing, elderly man. “Don’t worry, Father. I promise you I’ll take good care of everyone at home. I’ll look after Mother and Brother.”

Two days after his youngest daughter left his bedside, my grandfather passed away in the early morning. Auntie said that though she never forgot her promise to her late father, she never had the chance to honor it when it came to Waipo. Then, Uncle fell ill and she realized that it was the perfect chance to finally fulfill Waigong’s last wish. Thus, for over half a year, Auntie devoted herself to Waipo’s care. Thanks to her dedication, Waipo put on some visible weight and Uncle found the strength in him to battle against cancer.

So, even though she was now effectively trapped at home every day, mostly isolated from the world, my aunt said that she was rather happy with her lot. She’d finally been able to take on the heavy responsibility of looking after the most vulnerable members of our clan. She’d yet to tire of this alleged burden.

—

Now, Waipo was down with Covid-19. In her first week battling the infection, her body temperature oscillated between 38 degrees and 36 degrees, only dropping briefly when she took her medicine. Every time it wore off and her temperature went up, our family’s collective heart sank. We kept track of her condition in our WeChat group, with my aunt in charge of uploading nursing records daily: “Body temperature a.m. check: 37.8 degrees”; “I fed her two eggs and a bowl of milk porridge at 10 a.m.”; “Body temperature check at 2 p.m.: 38.3 degrees”; “She struggled to swallow her anti-inflammatory drugs, so we gave her a shot instead…”

On the 10th day of her fever, all Waipo could take was two spoonsful of water—everything else she refused. Auntie hurriedly call my mother, asking her to rush over and help. However, Mom was facing another family emergency. My paternal grandmother, Nainai had also been infected with the virus. Her high fever had never relented; her throat was irrevocably clogged with phlegm. Her condition declined steadily until she passed away on the night of December 25. At the time Auntie called, Mom was dealing with her mother-in-law’s burial arrangements.

Eventually, a family group call took place—on one end, my youngest and eldest aunts, now barely recovering from the virus themselves; on the other end, my mother. Being the middle child, Mom naturally had to pay heed to her eldest sister’s thoughts on the whole situation before voicing her own. Furthermore, as Waipo’s tireless caretaker, Auntie also took precedence over Mom on this particular occasion.

Dayi, my eldest aunt, said resolutely: “I’ve talked this through with Brother and his wife. Come what may, Waipo is staying here. We are not taking her to the hospital. Period.”

Auntie seemed less certain, and gave herself the floor before Mom could even reply. “What if this can’t be treated at home?”

Rather than answering directly, Dayi finally turned to Mom. In fact, my mother agreed with her. She thought Waipo was much too frail, what with being 95 years old and everything, to stand a chance at the hospital.

Dayi went on to share what she’d found online: “Hospitals are so crowded, apparently it takes hours now just to get a CT scan. Imagine parking Mother there for a full day while they stumble and fail to find the right treatment for her. She’d be done for, for sure.”

Mom said her mother-in-law never went to the hospital. She’d been under the care of my paternal aunt, who held Dad in great regard and respect as the eldest son and therefore followed his instructions on how to proceed should Nainai reach a critical condition. “If her time comes, let it be in the comfort of her family home.” When this moment came indeed, Nainai passed in the arms of her daughter at home.

Auntie is not a strong-willed person, and she found it much too hard to reason against her two elder sisters. In the end, she reluctantly and somewhat passively agreed that they would not send Waipo to the hospital.