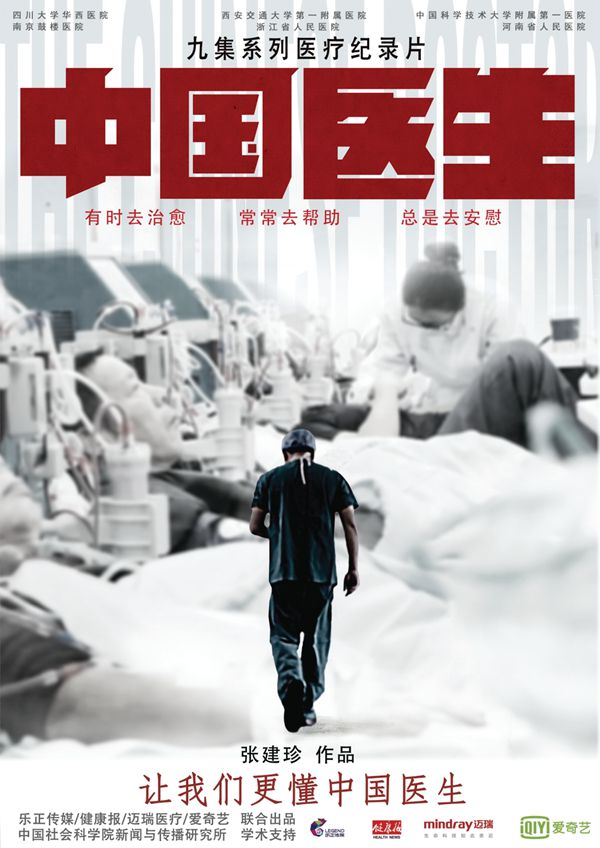

Acclaimed documentary series on Chinese doctors gains new relevance during Covid-19

“My heart is calm, knowing it is my duty,” wrote a Wuhan doctor on Weibo as she entered a 24-hour on-call shift on January 20. “Actually, I’m scared, but I must put on a brave face and charge to the frontlines.” In less than a day, the post received 600,000 “likes,” heralding the nation’s new recognition of the medical profession amid Covid-19.

In recent years, China’s medical sector has been mired in myriad scandals, with doctors even becoming victims of deadly public rage. Yet against the backdrop of the pandemic, the documentary series The Chinese Doctor (《中国医生》), which received little fanfare when it premiered on CCTV last May, has grown into a runaway hit on the iQiyi online video platform this spring, rated a superlative 9.3 out of 10 on movie review app Douban.

Originally shot in 2017, the documentary was inspired by director Zhang Jianzhen’s curiosity about those who pursue an often thankless profession. The first episode opens with Dr. Zhu Liangfu, a neurologist at the Henan Provincial People’s Hospital, recounting the wife of a deceased patient threatening to “rip him into shreds” before comically asking him if he can take her blood pressure.

The series, composed of nine 45-minute episodes, follows around a dozen doctors and their patients’ families at six hospitals in richer as well as poorer provinces, showing the unique challenges of each. In the well-resourced Nanjing Gulou Hospital, which has a piano in the lobby, a man withdraws his father from treatment due to cost. Dr. Xu Ye, finding his patient’s bed empty, is depressed to learn that the old man has been transferred to a local clinic that does not have the equipment to treat his full-body burns.

The incandescent lights of hospital hallways illuminate many of life’s brightest and darkest moments, and doctors emerge not godlike, but woefully human. Like a one-act play, each stand-alone episode of The Chinese Doctor chronicles the twists and turns that unexpectedly and heart-wrenchingly unfold inside different wards across the country, unifying them under themes such as “Hope,” “The Contract,” and “Fast Decisions.”

Medical procedures become windows to larger human and social dynamics; hospitals are not only sites of pain, but hotbeds of compassion. On the floor of a hallway in Sichuan West China Hospital, a couple sits in suspense for the result of their infant’s expensive surgery. The father explains to the camera, “To be honest, we probably can’t save that much money in our entire lives…but we can’t say the words ‘give up’ to our child.”

In Xi’an, a couple took in a child with a cleft palate, who had been left outside their home in a blanket. Moved by their selflessness, cosmetic surgeon Dr. ShuMaoguo funds the infant’s cleft-lip operation by appealing for donations on WeChat. The emotional palette of the show is rich, teetering between helplessness and hope, but almost always ending in triumph. The heart is duly warmed, though the head still questions how cherry-picked these stories may be.

The show is at its least emotive when it caters to politics. The last episode, titled after President Xi Jinping’s slogan “Never forget our original aspirations,” features a prominent gynecologist who was once an itinerant village “barefoot doctor,” and a graduate of the Academy of Surgery in France, who chose to return to China to serve Chinese patients. Unbacked by the vivacity and vulnerability that defined other episodes, these two seemingly powerful subjects fail to come alive on the screen, and at worst, feel performed.

Director Zhang Jianzhen hopes the series can restore trust in doctor-patient relationships

Compared to most medical dramas, the show’s portrayal of the profession is unexaggerated, though still sometimes veers into sentimental territory. Hardcore cinema vérité fans may be turned off by the piano and strings soundtrack, which drum up suspense and croon over tears. Yet for the most part, the show leaves its gut-punches to the details: a mother’s last bath with her young son before he is sent into the closed leukemia ward for surgery; a baby with a cochlear implant whose eyes light up as he hears sounds for the first time.

In the cycle of art imitating life imitating art, the most significant compliments to the show, according to director Zhang, came with letters from young viewers. “Many medical undergraduates have been reluctant to become doctors in these years,” Zhang recalled in a February interview with the Beijing Daily. “The students wrote to the doctors in the film, saying they will continue their studies to become clinicians.”

Now under Covid-19’s spotlight, the medical profession may be finally getting its due—on and off the screen. Since January, doctors at the Beijing Ditan Hospital have been serenaded by Covid-19 patients to the song “Grateful Heart”; food delivery workers have taken donations of meals to hospitals, with extra dishes and notes of encouragement from the restaurant or customers; and the entire nation grieved the passing of Dr. Li Wenliang, the Wuhan ophthalmologist who raised alarm about the virus in December 2019.

Chinese audiences have long been owed a level-headed representation of the medical profession—portraying doctors neither as “angels in white” nor as money-sucking leeches, but flesh-and-blood people who take responsibility for others’ well-being, and hold on to their own lives as best they can. –Tina Xu(徐盈盈)

Dr. Zhu Liangfu: What relation are you to the patient?

Shì tā shénme rén?

是他什么人?

BaiShaozheng: His son.

Érzi.

儿子。

Dr. Zhu: Do you understand the risks we’ve stated?

Nǐ lǐjiě wǒmen shuō de zhèxiē fēngxiǎn ma?

你理解我们说的这些风险吗?

Bai: I basically understand.

Jīběn lǐjiě.

基本理解。

Dr. Zhu: Do you agree to the surgery?

Nǐ tóngyì zuò shǒushù ma?

你同意做手术吗?

Bai: I agree.

Tóngyì.

同意。

Must-See Movies and Series

In Wuhan

Created by Figure, a short video brand that specializes in profiles of trailblazing individuals, this timely documentary series takes the audience to the eye of the storm: Wuhan, the city hit first and the worst by the Covid-19 epidemic. Two 17-minute episodes have been released at the time of writing, focusing on volunteer drivers and delivery workers, locksmiths suddenly in high demand to save pets trapped in apartments, and a barber giving free haircuts to doctors. The documentary began shooting in late January from the epicenter of the outbreak at great personal risk to the production team, and although it has been criticized for a lack of depth, it remains an inspiring look into how ordinary people in Wuhan live and cope with the crisis.

And Yet, the Books

The five-episode documentary is an ode to reading, produced by and streamed on Bilibili, a major Chinese web platform known for animation, streaming videos, and various sub-cultures. Its episodes cover the ins-and-outs of book publishing, design, and distribution, and the lives of avid readers. It focuses on individuals such as Zhu Yue, a novelist and literary editor who strives to publish and promote original literature, and Xiao Yin, a popular book reviewer who hosts a video broadcast. Narrated by actor Hu Ge, this documentary series takes a deep look at book-reading culture in our technology-saturated society, and finds that it is alive and thriving.

The Firsts in Life

This documentary series captures 12 milestone life events of ordinary Chinese, including the underprivileged: birth, going to school, marriage, purchasing a home, retirement, and facing the end of life. In the episode “Growing Up,” “left-behind children” in rural Yunnan fall in love with writing poetry. In another episode, “Going to Work,” disabled individuals take up jobs as online customer service agents for the e-commerce conglomerate Alibaba. Produced by China Network Television and the Shanghai Media Group, this series can be watched for free on cctv.com, Tencent Video, Bilibili, and Youku.com.

Lost in Russia

The fourth film in Xu Zheng’s “Lost” series, this road-trip comedy revolves around a mother and son’s adventures on a trans-Siberian slow train. Xu Yiwan (Xu Zheng), a divorced businessman, is guilt-tripped into taking his estranged mother Lu Xiaohua (Huang Meiying), a former nurse in the Chinese embassy in Moscow, on a journey to realize her lifelong dream of singing a solo at the Red Star Theater. Much of the humor originates from the strained mother-son relationship, as well as the exotic setting. The film’s initial cinema release was canceled ahead of Chinese New Year due to the Covid-19 outbreak, and it was sold to ByteDance for free online streaming. Lost is now available to view on Xigua Video and Huanxi Premiere. – Liu Jue (刘珏)

Angels’ Advocates is a story from our issue, “Grape Expectations.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.