Polarizing new rap show promotes “gentle” lyrics and serious themes

On a stage accompanied by traditional Chinese instruments, Sheng Fan raps about midlife crisis. “Look, time flies like an arrow, having sons and daughters…/ After breaking the cocoon into a butterfly, I’m in my 30s, toasting to the passing years,” croons the Beijing-based artist in a suit and tie, looking more like a hotel manager than the co-founder of an underground hip hop group.

Based upon the Chinese idiom, “A man should be independent by the age of 30,” Sheng Fan’s song “Independent” recently won a rap battle on new reality show Rap for Youth, against a rival who rapped more conventional lyrics bragging about himself and his passion for hip hop.

Subverting the tradition of its genre, in which performers stand eyeball-to-eyeball “dissing” each other and flaunting their own skills, Rap for Youth, which premiered on youth-friendly streaming platform Bilibili in late August, puts forward the slogan “Everything can be rapped.”

This approach has won over viewers who were originally not interested in rap, as well as mainstream media who’ve applauded the “wholesome” values—while polarizing the opinion of long-time fans who question whether “authentic” rap can survive China’s tightening controls over the genre.

From the trivialities of life, to issues of war and peace, to issues of the heart, anything goes on Rap for Youth. Female rapper Yu Zhen sang about the sexism encountered by her friends, and encouraged them, “Do not give much thought, don’t listen to anyone else, you’ve done really well.” Another competitor, subs, sang about family problems to orchestral music in “Draw”: “I want to draw a house, with parents who don’t quarrel at home…I want to draw a comfortable city and let everyone find their home.”

The diverse lyrics and performance styles have won waves of praise for Rap for Youth. Only in its third episode at the time of writing, it has received 8.9 points out of 10 on Douban, one of China’s most popular review-aggregation websites for film and television. By comparison, the third season of China’s first rap-focused reality show, The Rap of China, only earned 4.6 points over the same period.

Hip hop culture entered China in the 1980s, though professional rappers and groups only began to emerge in the 21st century. Most early Chinese rappers were directly inspired by their Western counterparts in lyrics and form, expressing a confrontational attitude and rebellion against mainstream culture. Their works have tended to focus on themes like dissing haters and the pursuit of fame and fortune.

In 2017, the first season of The Rap of China aired with the unofficial slogan “Keep real, man!” Competitors made no effort to hide their pursuit of creature comforts, and always dissed back when they were attacked by fellow contestants.

The development of Chinese hip hop culture suffered a severe blow when PG ONE, soon after winning the first season of The Rap of China, was accused of encouraging young people to take drugs and insulting women in his songs. This was followed by scandals in his personal life that led to a media blackout: PG ONE’s music was removed from major streaming services, and he has never since appeared in any TV programs or public performances on the mainland.

The fallout even affected PG ONE’s co-champion GAI, whose scenes had to be hastily deleted from the musical talent show Singer, which he had been shooting at the time. In January 2018, China’s State Administration for Radio, Film and Television issued a ban on the appearance of artists with tattoos, rappers, and other forms of “non-mainstream culture” on TV. PG ONE’s label, HHH, one of the most famous hip hop labels in China, was disbanded a year later. Chinese rappers began to create songs with positive messages and collaborate with pop stars to attract the public, such as GAI’s patriotic “The Great Wall,” “Chinese Civilization,” and “Uphold the Honor of My Ancestors.”

Before he wrote “Independent,” Sheng Fan also created what he called “gangsta rap songs” with violent elements. “My previous music was more like a knife, but now I don’t want to stab anyone; my knife is not that sharp anymore,” he said on the show.

On the other hand, despite the lack of swear words and hostility among the contestants, performances on the show tackle hot-button social problems such as school violence, depression, and sexism. “This is real Chinese rap. This is rebellion by adults,” critic Yan Dong wrote in China Newsweek magazine of Rap for Youth contestant Doggie, whose song “Real Life” touched on school bullying, and the recent college admissions scandal where children of powerful officials were found to have stolen the identity of high-scoring rural students in order to attend university.

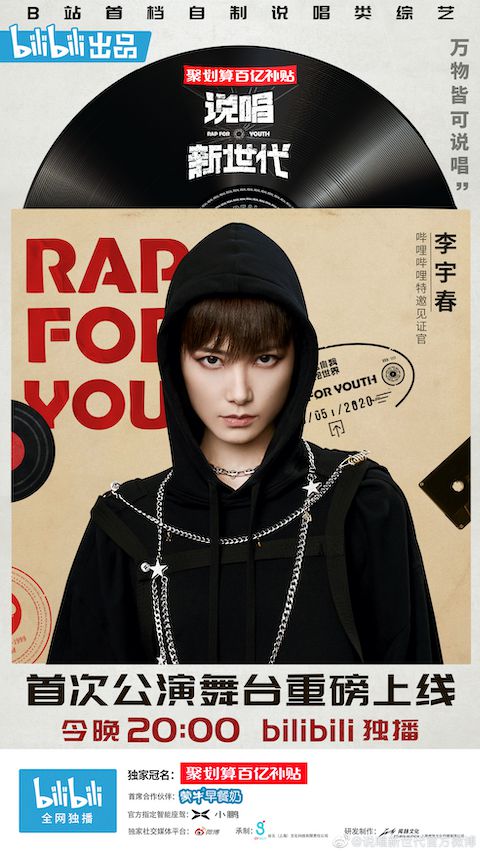

Poster for ‘Rap for Youth’ featuring pop singer Li Yuchun, one of the mentors on the show (Weibo)

Chinese singer Li Yuchun, a mentor on the show, noted that Rap for Youth gives a distinct Chinese aesthetic to an imported art form. “The new generation of rappers are making their own sound, which come from life and are no longer in the shadow of foreign cultures, nor are they following or imitating classics,” she said in the show’s first episode.

Yet some critics of the show balk at the idea that “Chinese rap” must be gentle. In response to the question “Why has there been such polarizing reactions to the song ‘Draw’ by subs on Rap for Youth?” on question-and-answer platform Zhihu, a user wrote, “In terms of writing, although it has enough positive energy, it piled up big words one after another, like a composition of an elementary school student but without the imagination of an elementary school student.”

Others disagree with the style of rap seen on the show, which negative reviews have compared to “poetry recitation.” “Rap has rhythm and pitch, but this song’s rhythm is hard to describe,” wrote a Zhihu user of “Draw.” Another wrote, “All [other answers] say the content and direction of the song are good, but that just means the lyrics are good. If you associate it with rap, that’s being disrespectful to both [the genre and the song].”

Fans defend the show by arguing that rap is a constantly evolving and inclusive genre. “The slogan ‘Everything can be rapped’ has given new life to the critical spirit of rap in China, and that is why it can stand out and be accepted by the wider public,” noted a recent WeChat essay published by the Online Video Research Center at the Communication University of China. On the show itself, rapper Jiang Yunsheng reflected, “In the past, I regarded music as a competition, and the judging criteria were only good and bad. But slowly, I realized that music should be more inclusive and one should not judge other people’s art.”

Critic Yan believes Rap for Youth signals the maturation of Chinese rap. “The stage where Chinese rap is now is like the first transformation undergone by American hip hop,” he wrote in China Newsweek, pointing out that American rappers had also evolved from dissing and rebelling for rebellion’s sake to making political and social critiques.

“Rap doesn’t have to be shocking, but has to be novel; it doesn’t have to flaunt wealth, but it has to be subversive; it doesn’t have to be fast, but it has to be free and easy,” wrote commentator Zou Xiaoying for Sanlian Life Weekly magazine. Rap “has to be interesting. If it’s not interesting, what’s the point?”

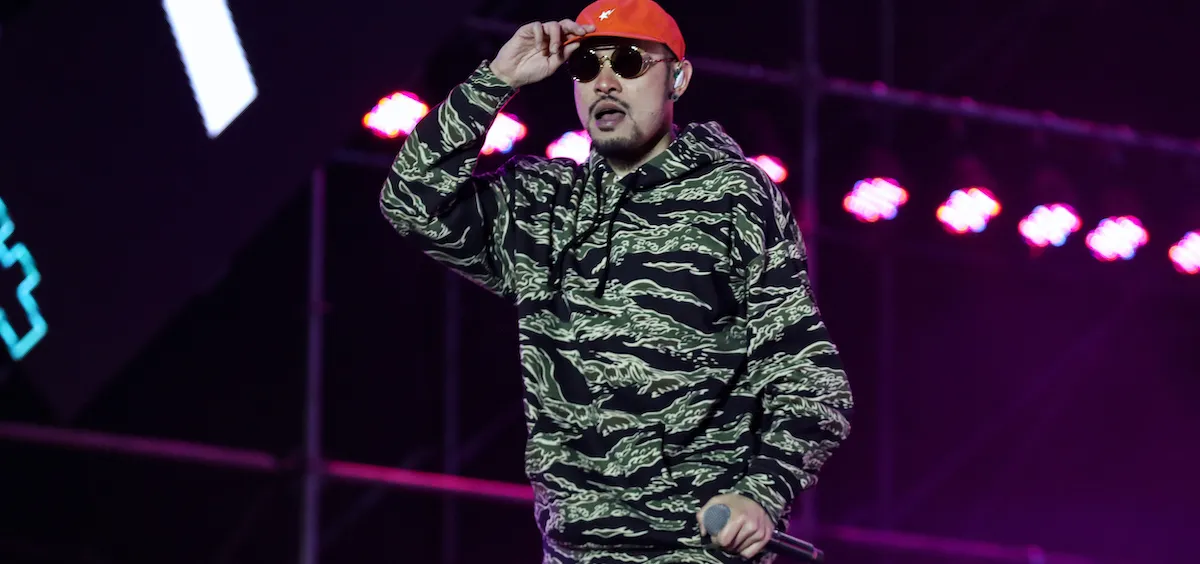

Cover image of MC Hotdog in 2019 Yaoyo trend culture festival