A humble studio is home to a history of photography in China

If you have never been to China Photo Studio (CPS), you may be surprised that, in such a digital era, people are still willing to queue for hours to have their photo taken. For many, a portrait requires more than just a digital camera or a smartphone. “It’s about quality, aesthetic taste, and a sense of ritual,” says Bao Chen, marketing manager of CPS.

Located on Beijing’s Wangfujing Street, one of the most prestigious commercial areas in all China, China Photo Studio keeps an exceedingly low profile compared with the other fancy restaurants or luxury retailers. Its signage, hidden among the many outsized façade for Louis Vuitton and Quanjude Roast Duck, was designed in an age of simplicity—just five red characters, “中国照相馆”. But anyone who reads the plaque outside may be in for a surprise: For this humble studio is one of “the top 10 enterprises of the national photography industry.”

When I visited, it was 10 o’clock on a Friday morning, and customers already crowded the reception. They followed the instructions behind the counter to pay their bill on the first floor and take photos on the second, and wondered where they could go to pick up the prints. “Today is not a ‘busy’ day! It’s not a weekend, nor the holidays!” Bao told me. “If you come here during Spring Festival, you’ll see people lining up from early morning.”

Lady Shanqi, one of the many wives of Prince Suzhong of the First Rank, poses in this early 20th-century portrait (Fotoe)

During the previous Chinese New Year, the Beijing Morning Post reported, CPS took an average of 300 orders per day, in person. For many old Beijingers, a studio photo of the family has become part of festival tradition. After 60 years in the business, CPS is a household name among locals. “People trust a time-honored brand,” explained Bao.

What’s less well-known is that CPS actually started in Shanghai, and achieved nationwide fame in the coastal city before moving to Beijing. According to Heavenly Lights, Cloud Shadows, an in-house history book of the studio’s last eight decades, the studio owes its founding to a love affair. In the 1930s, Wu Jianping, a young man from Jiangsu province apprenticed to a Shanghai studio, fell in love with his colleague He Dingyi. But He’s father thought Wu was too poor for his daughter. Determined to prove He’s father wrong, Wu set up the first branch of CPS in 1937 on West Nanjing Road, the busiest street in Shanghai. Eventually, Mr. He relented.

China Photo Studio’s big break: Wu’s famous portrait of Nancy Chan, a rising movie star in the 1970s (courtesy of China Photo Studio)

At the time, Shanghai had several foreign concessions, and most studios were named using characters that evoked Western products. But the Lugou Bridge Incident had just occurred, sparking the war, so Wu decided to give his studio a patriotic title: “China Photo Studio.” Despite his pride, there wasn’t much to boast of initially: Two triplex cameras and a four-story house that served as studio, darkroom, and staff quarters for about 10 staff, including Wu and He. In the first two years, Wu was barely able to make rent.

Wu’s fortunes turned when he was given the opportunity to photograph Chen Yunshang for the 1939 movie Mulan Joins the Army. Also known as Nancy Chan, Chen was a rising star considered a “beauty in the south, unparalleled on Earth.” The movie’s producers planned to use the eight-inch photos as giveaways to ticket holders, and decided to cooperate with CPS. Wu printed China Photo Studio’s name on each of the photos and displayed 20 enlarged versions in the studio’s window.

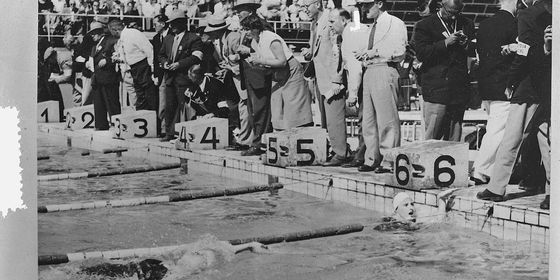

In 1956, China Photo Studio opened its first Beijing studio at Number 4, Wangfujing Street (courtesy of China Photo Studio)

The movie did extremely well, with over 50,000 portraits sent out to Chen aficionados, and helped establish CPS as a recognizable brand in Shanghai. “At the time,” author and collector Tong Bingxue notes in his 2015 book A History of Photo Studios in China (1859-1956), “many upper-class ladies, popular dancing-hall stars, and even powerful gangsters would feel proud just to have their portraits displayed in the China Photo Studio window.”

Yet just a few decades previously, photography had been regarded as an exotic, foreign technology; some even associated it with sorcery.

French artist Louis Daguerre unveiled the first daguerreotype process in 1839, and the Canton Press, a Macau newspaper, announced the discovery to China just two months later. But it was not until 1842, according to Tony Bennet’s History of Photography in China, that the first cameras arrived in China, courtesy of two British men mapping the Yangtze river. Another three years later, American photographer George West set up the first commercial photographic studio in Hong Kong in 1845.

In the mid-50s, so many apprentices came to study photography at CPS that the course had to be moved to a warehouse to accommodate the influx (courtesy of China Photo Studio)

In the 1860s, when Qing diplomatic missions were sent to visit Europe and America to bring back technological knowledge, Chinese-owned studios began to appear. The first were mainly concentrated in Hong Kong and neighboring Guangdong province, before gradually spreading north. Tong calls this process “the Guangdong effect.”

In his essay “On Photography and So On,” the writer Lu Xun describes the views many Chinese took of the phenomenon: “[It] seems like witchcraft. In one province, during the reign of the Xianfeng Emperor, someone had their property destroyed by villagers just for taking photos of people.” China’s Folk Taboos observed that Chinese people “believe shadows are not only part of one’s body but related to one’s health…the shadow may be one’s soul…if people lose their shadows, they lose their life.” This belief included the idea that mirrors drained the soul: “The more one looks in a mirror, the faster they will age.” Not surprising, then, that photography was thought to steal one’s soul.

A photo artist at CPS coloring a black-and-white photo (courtesy of China Photo Studio)

These superstitious beliefs were even used by swindlers to perform simple cons. Tong describes one common scam in which a “magician” approaches an invalid, explains that his illness is caused by a demon, and offers to expel the creature. The patient is brought to a photography studio, where a photo is taken—the blurry image, it’s explained, is the demon, now expelled. Some cults also used photographs of religious iconography to fool their followers in believing that gods existed in the mortal world.

It wasn’t until book such as Practical Photography and Developing Miracles were published in the early 20th century that Chinese people were able to learn more scientific explanations for the new technology. Cost was another barrier. “Back in those days, only rich people could afford to take photos,” Zhao Zengqiang, deputy manager of Beijing-based Dabei Photo Studio, established in Peking in 1921, tells TWOC. As Dabei was famous for “theatrical-costume photography”—in which customers would pose in elaborate Peking Opera outfits and makeup—their main customers were actors and piaoyou (Peking opera aficionados, often amateur performers), as well as prostitutes from the famous bawdy Bada Hutong. “Only rich people could afford to appreciate opera,” Zhao says. “And the prostitutes were not only rich, but interested in fashionable things.”

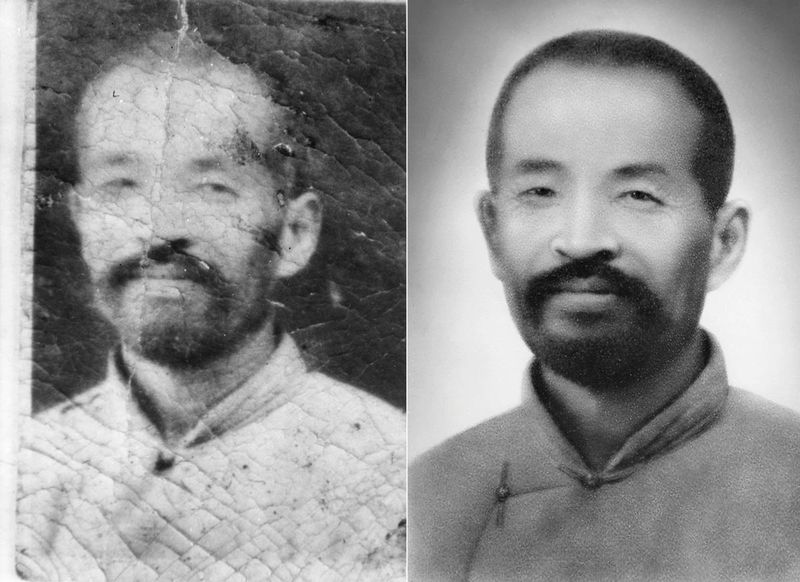

One of CPS’s specialities is image restoration and editing of portraits from an era before Photoshop (courtesy of China Photo Studio)

Still, compared to Shanghai with its ports and foreign concessions, Peking lagged in terms of modishness and modernity, and the outbreak of war in 1936 effectively halted much of the industry’s growth. It wasn’t until the spring of 1956 that CPS landed back on the fashion radar, after an Indonesian ambassador complained to the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs that he’d had a suit altered 21 times at a Beijing tailor, and still couldn’t get a decent fit. Premier Zhou Enlai, himself a snappy dresser, decided that the capital’s service industry required an urgent boost, and ordered a list to be collated of the country’s best clothes shops, barbers, and photo studios to move to Beijing.

That year, 19 CPS staff moved to Wangfujing, a move that ultimately proved no great hardship: Heavenly Lights claims that one married couple working in post-production, Wu Renlin and Huang Yuehua, together made more than Chairman Mao’s official salary. The studio’s photography style made a big splash in Beijing. Many leaders visited, and Zhou Enlai used his studio portrait as an official photograph; his wife Deng Yingchao displayed it on his tomb after his death in 1976.

A CPS photographer takes a wedding photo for a young couple in the 1990s (courtesy of China Photo Studio)

The Dabei studio, hired to photograph both the 1956 National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, enjoyed similar success. When TWOC first contacted Dabei for comment, they replied all their photographers were busy taking pictures for the 19th CPC National Congress.

Photography’s newfound prominence would come to haunt it a decade later, as the 10-year Cultural Revolution tried to eradicate any business or person thought to belong to one of the “Four Olds”—Old Customs, Old Culture, Old Habits, and Old Ideas. Considered bourgeois and a luxury, studio photography was also targeted. CPS was forced to hide its famous color portraits in order to prevent their seizure. Dabei’s opera costumes were destroyed—the only music permitted were socialist “red” operas, in which performers wore military uniforms or simple costumes; portraiture, wedding photography, makeup, and post-production work were forbidden. “It was impossible to display a photo of a beautiful woman in qipao with their thighs shown,” says Zhao.

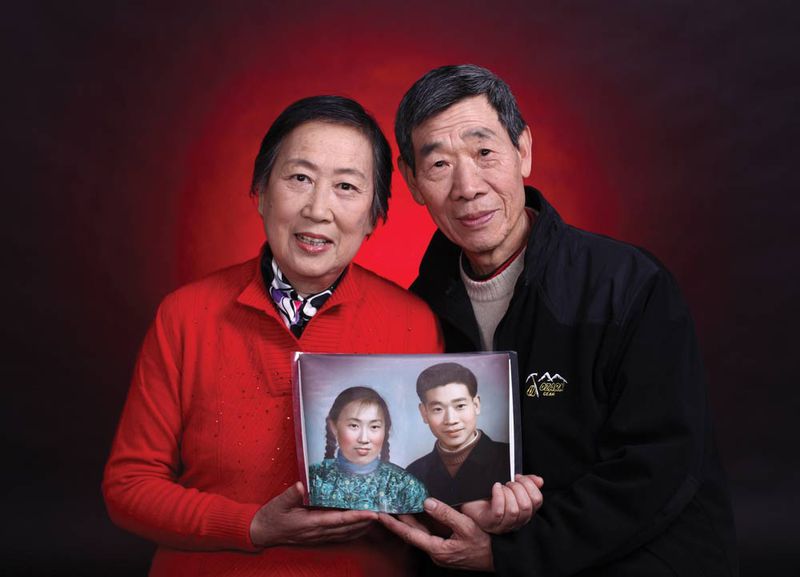

A couple’s golden wedding anniversary photo taken at China Photo Studio in which they hold their original photo taken at the same studio (courtesy of China Photo Studio)

The only permissible shots were full-face pictures, or poses reading the Quotations from Chairman Mao. For years, photo studios like CPS and Dabei only survived by taking photographs of Red Guards in Tian’anmen Square as souvenirs. It was only when economic reforms began in 1978 that color photography and pre-wedding portraits flourished again. The latter usually came in batches of four, taken by the bride and groom before their nuptials, sitting, standing, and separately. “The pre-wedding photo was very popular,” said Zhao. Nine out of 10 couples traveled to Beijing from elsewhere—“from places all over China, because Beijing’s photo studios are the best.”

Despite the prevalence of modern studios, digital cameras, and mobile phones, the likes of Dabei and CPS remain popular today. Indeed, their old-fashioned approach has proved something of a draw. One of Dabei Studio’s most popular products are black-and-white headshots of children. “They’re extremely popular among young parents born in 1980s and 1990s,” Zhao told TWOC. “At our busiest times, they’ll come in the early morning and line up for three hours to take a photo. I think the reason is just we’re good. We can create high-quality photos.”

Dabei studio was famous for its “theatrical-costume photography,” and wealthy opera lovers, as well as their courtesans, frequently visited (courtesy of Dabei Photo Studio)

Bao agreed. “I think the most important thing is the spirit of craftsmanship. Technology has changed. In the past, our workers processed photos by hand. Today, we use computer software. But the aesthetic taste and spirit are consistent. It’s inherited from old generations.” A father of a young boy, Bao said he might take his family to a modern studio occasionally. “But we will take a photo every year here in China Photo Studio. It has different meaning when doing it here.”

A Long Lens is a story from our issue, “Fast Forward.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.