The search for the best comfort food in the late-night dining capital of Asia

It’s pouring rain again in Taipei. Not a run-of-the-mill drizzle, or even a strong thunderstorm. Sheaves of water heave and ho before my eyes—bristles that slash with the fury of an angry painter.

Although I am tucked safely away under an eave, I can feel the pounding of the rain on the pavement; it strikes with such force that the residual drops hit me like little needles stabbing at my skin, and the blaring neon signs just across the street are turned into fuzzy halos of red and blue. Thank God I wore flip-flops.

Nobody will be going anywhere any time soon, so I figure it’s the perfect time to eat. Under the dry awning of the restaurant, ponchos come off, umbrellas are shaken of excess water, and hats are wrung out as my eating companions arrive, and we finally sit down atop plastic stools at the undecorated wooden table. I pick up the plastic clipboard from the table, and stare at the rows of delectable choices on the menu.

Taiwan is an island of over 23 million people, with 16 recognized indigenous ethnic minorities and an equally varied geography—from plains to beaches, forests to mountains. With such a lush climate and diverse population, it is known as a culinary hotspot, despite stiff regional competition for the title.

I came here in February to play in the band at Taipei Stadium with singer A-Lin, and I am still here at the end of May, during the rainy monsoon season. Since we were unable to return home to Beijing after our show, I hunkered down in my hotel to wait out the Covid-19 pandemic. After a few weeks, when the rate of infections slowed to zero, I began to venture out.

While Taiwan is famous for its food, most short-term visitors to the island are familiar with the yeshi (夜市), or night markets, only. In lieu of these bustling tourist attractions, replete with stands that hawk gimmicks and snacks (delicious, nonetheless), I wanted to know more about where to get the kinds of meals that always make my Taiwanese friends abroad declare their undying love for their island’s cuisine.

Rechao (热炒), or “hot-fry,” are the sort of working class restaurants that are cheap, open late, delicious, and have a rich and storied cultural background. The one we’ve chosen tonight is quite famous among Taipei residents, called Pin Xian.

The area, Linsen Park, is known as a red-light district, and not coincidentally peppered with famous rechao that are open late, often past 1 a.m. If Taipei’s gleaming Xinyi District is Manhattan’s SoHo, then this is Taipei’s Lower East Side: a grimier part of town, where you’re likely to get dripped on by the air conditioning units hanging off the mildewed art deco facades of low-rise buildings.

Famous among the locals in Taipei, Pin Xian rechao restaurant is packed with diners

Measures to combat Covid-19 had taken a huge toll on the local economy, but Pin Xian is positively bustling on a sopping wet Tuesday evening. Groups of friends and colleagues cram together at the low tables, while others wait for tables under the eaves outside. Beer comes out; glasses stacked on the table. We order. The best thing about many rechao: No dish costs more than 150 NTD (35 RMB).

Although the night market culture in Taiwan is upheld as a gold standard of cultural preservation in the modern world, locals rarely rave about them. “Sure, they’re fun,” one of the Taiwanese violin players told me during rehearsal back in February, “but they’re not even that representative of Taiwanese food anymore. Too many swirling potatoes and bratwurst stands now,” she said, rolling her eyes.

If yeshi is the chic model of Taiwanese culture, then rechao is its hairier, less glamorous urban cousin: a place that serves the utilitarian purpose of feeding easy comfort food, amid a pleasant social backdrop. While the history of Taiwan’s night markets as centers of commerce begins in the 1950s with industrialization and migration to the cities, rechao’s story began in the 80s, during Taiwan’s “economic miracle,” when office workers in a highly industrialized urban economy began to need quick, cheap, and flexible fare for late nights.

The invention of the canister-based gas tabletop cooking system allowed more dishes to be served while literally taking the heat off the kitchen. The fare may be a mix of the cuisine from many cultures: Sichuanese, Fujianese, local Taiwanese, Southeast Asian, Japanese, and Korean; you may even find French fries on the menu on occasion.

Second Market in Taichung is home to commercial vendors as well as food stalls

The first of our dishes arrives: bitter melon stir-fried with salted duck egg, a culinary heritage of southern China; a fragrant pan-fried omelet with basil mixed into the egg; salty stir-fried clams in black bean sauce and peppers; and crispy slices of pan fried pork liver coated in a thick, dark, sticky-sweet sauce. Round one has begun. Shovel your own bowl of rice from the big steamer in the corner, and grab a guava juice or apple soda from the fridge. There’s also a selection of ice cream in a freezer by the fish tanks where people are fawning over the size of the cod.

More food arrives: boiled pork topped with tangy garlic sauce and cilantro; salmon sashimi; watercress with garlic; deep-fried tofu; and my personal favorite of the evening, steamed cod with a crunchy topping made from baked soybeans, garlic, peppers, ginger, and light soy sauce.

By the time we finish, we’ve gone through our fair share of beer. I can tell many of our neighbors have as well, by the way the laughter now reverberates through the open room. Rechao is the lifeblood of Taiwanese society: a place where friends or coworkers can banter and get a tasty morsel on either end of a night of heavy drinking. Friends gossip, colleagues gripe, couples break up, all against the backdrop of hissing woks and clinking glasses.

The rain has subsided a bit, though rivers still run down the street into the storm drains. I snap my umbrella open. I’m excited to see what other cities have to offer in terms of midnight eats.

Colonial architecture at the entrance of Second Market

The next day I find myself at Taipei Station at 11 a.m., waiting for Train 136 to Taichung. Originally designated as the cultural capital of Taiwan by the Japanese, who occupied the island after the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Taichung still has remnants of colonial architecture in places like the Miyahara Eye Hospital, now converted into an ice cream shop and tea house.

Taichung experienced a manufacturing boom in the 80s; while Taipei underwent an office revolution, this central city became Taiwan’s industrial heartland. And everyone I talk to says the food is even better there.

I’m here far too early to sample the late night fare, so I hail a cab for the city center. Second Market is one of two well-known open-air food markets in Taichung, and, among other laurels, boasts a famous stewed pork rice (卤肉饭) spot, so I head there to try my luck—some of these stalls are so popular that they open only for a few hours a day at lunch.

Inside the market, labyrinthine passages open onto plazas and halls lined with food stands; all are washed in decades of sunlight that streams in through the holes in the patchwork roof. Second Market is truer to the sense of the word than most night markets. An old man measures cloth for suits in a corner shop; another stall sells only scissors of every possible variety. The market’s role as a hub of light industry and commerce has hardly changed since the 1950s.

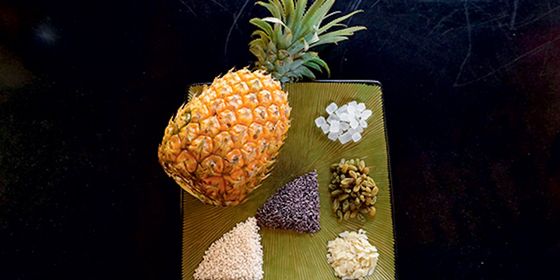

Rechao dishes like bitter melon, pork liver, and stewed pork rice draw culinary influence from many regions

During Taiwan’s post-war period of industrialization in the 50s and 60s, migrants flowing from agricultural areas to Taichung and Taipei also brought their hometown delicacies: as a result, night markets became well-known for their culinary delights. I suspect that international tourism being mostly focused on Taipei and the countryside has allowed the markets in an industrial center like Taichung to retain their role as places where people do business (and eat great food).

Stewed pork rice is offered at nearly every restaurant in Taiwan; all of Taiwan’s pork is farmed on the island, and strict measures protect the 2.5 million USD industry. For so many people to rave about one restaurant serving this ubiquitous dish is surprising. It doesn’t look like much: two spongy meatballs adorn a plain porcelain bowl of white rice, topped by the infamous sauce—a fragrant brown stew of melted fat and meat, with some green onions garnishing the top.

A bite, however, changes everything, and what looks like a pretty simple stew is actually the elevation of (most likely) centuries of culinary tradition. There is a lot of debate over the origin of the dish: in recent years, lu (卤) and its homophonic 鲁 (another name for Shandong province) are often interchanged. In 2011, the Michelin Green Guide attributed “鲁肉饭” to Shandong, touching off a fiery debate between food critics and historians.

Hunger satisfied, I take a walk around the Central district, despite the heat. In some ways, Taichung is a place where the aesthetics are still defined by utility; a store selling old audio gear (cassette tapes!) neighbors an old tea house. It feels like we’ve boiled down to the essence of a city without the trappings; compared to Taipei, Taichung feels like well-worn leather.

Business is in full swing at Taichung’s higherend rechao restaurants

Finally, I hop on a bus heading north. One Jiang, one of Taichung’s higher-end rechao, is already buzzing at 6 p.m. My companions and I order a cleansing cold dish of raw onions with cilantro and crisp pepper drizzled in Japanese soy sauce with ginger; crispy deep-fried bitter melon adorned with peanuts, hot peppers, and onions; a tornado omelet in fish sauce; sweet and sour pork ribs; and a classic Chinese pork dish braised with vegetables preserved in soy sauce.

By far, the standouts are the deep fried oysters with basil (how do you manage to give fried oysters such intense floral notes?) and my personal favorite of the whole meal: the underrated “egg-flavored cabbage.” The white leaves are chopped and stir-fried with garlic and browned egg bits akin to the scrapings of an omelet, which somehow impart a rich, buttery flavor into each morsel. The total for our meal comes to just 1,700 NTD (400 RMB).

By now, business is in full swing. Across from me, I see a family of eight diving into seafood hot pot. Elsewhere, an elderly man is pouring out his fifth glass of a bottle of Kavalan whiskey (his wife is already working through her third) over a tray laden with giant orange shrimp. Someone’s got a promotion: a company party in the corner is toasting with beer. In places like this you realize very little has changed, despite the lingering specter of the coronavirus.

During the hour-long ride back to Taipei, I reflect on the differences in the culinary experiences of Taipei and Taichung, even down to the type of hot sauce that is abundantly available at each meal: the former, a garlic-chili mash, less blended than a simmered-down reduction of all the key ingredients; where the latter seems to be a sweet chili sauce more reminiscent of Thai seasoning.

But beyond that, there is a deeper, more significant difference in the culinary identity that emerges from the cultural hodgepodge that makes up the late night fare of two cities just a few hundred miles apart. Although rechao establishments differ little in decor, in one city, food is fast, urban, and unembellished, equal parts nourishment and company; in the other, it evokes a pastoral experience, of making time for a meal as opposed to rushing through. As cliché as it may sound, perhaps there is something to be said about the particular cultural milieu that forms the identity of each city and influences its culinary experience. Fast and slow food, the city and the suburbs, the cubicle and the belt-line—the island’s food culture caters to it all.

Cover image from VCG

“Midnight in Taipei” is a story from our issue, “High Steaks”. To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.

Midnight in Taipei is a story from our issue, “High Steaks.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.