Why Chinese companies give out non-cash gifts for the holidays

Chinese travelers may be arriving home this lunar new year with slimmer “red packets” than usual, as a recent survey reports that the percentage of white collar workers receiving year-end bonuses have halved since 2017.

Only 33 percent of respondents to Zhilian Zhaopin’s “2019 White Collar Annual Bonus Survey” expected to receive year-end bonuses (年终奖) in 2019, compared to 55 percent in 2018 and 66 percent in 2017. But the job-hunting website did find increased “exoticness” in the non-cash rewards that employers gave out this year: condoms, expired calendars, hammers (symbolizing “breakthrough”), and weight-loss courses, in contrast to tamer gifts like eggs, pork, and towels from last year.

A hardworking TWOC web manager collects his reward for the year

Nianhuo (年货), literally “new year goods,” are a wide range of non-cash items that Chinese families traditionally prepared ahead of the Spring Festival—including food, new clothes, home decorations, and gifts for relatives and friends. This annual shopping spree not only brought home useful items for the holidays, but symbolized prosperity for the year ahead.

According to the Official Rites of the Han (《汉官仪》), a book of imperial protocol from the Eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220), Chinese emperors distributed cash bonuses as well as gifts such as beef and rice to their ministers during the last lunar month. During the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1279), ministers’ year-end gifts included goats, flour, rice, and alcohol.

Under the PRC’s planned economy (1956 – 1992), some state-owned enterprises distributed extra food and coupons ahead of the Spring Festival, but the corporate nianhuo tradition really revived with gusto during the reform period: In 1978, according Qilu Weekly magazine, employees at the Guxian County Reservoir of Henan province received 10 kilograms of apples, 5 kilograms each of peanuts and walnuts, 3 kilograms of meat, 2.5 kilograms of flour, 1.5 kilograms each of rice and eggs, 0.5 kilograms of sugar, a bottle of alcohol, and a cigarette apiece—all coveted items that had to be purchased with ration coupons at the time.

According to Zhilian Zhaopin, the most common year-end bonus in 2019 was cash (received by 91.1 percent of respondents), followed by daily use articles (8.6 percent) and food items (8.4 percent). What most employees wished to receive was cash (94.8 percent), followed by apartments and cars (12.6 percent), and company stocks and shares (12.3 percent).

Among food items, rice, dairy products, cooking condiments, nuts, fruits, and snacks such as chocolates and biscuits appear to be classic nianhuo standbys, judging by sales figures from e-commerce website JD.com’s annual “Nianhuo Festival.”

Some employers, though, have long sought to break this mold: In 2008, a farmer’s market in Hangzhou awarded its employees a cabbage each. In other years, Weibo users have reported getting medicine, socks, menstrual products, and live chicks—sometimes in lieu of cash.

“Year-end bonuses are supposed to be positive reinforcement [for the employee],” sociologist Hu Guangwei of the Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences told Sichuan Online after a 2014 debacle, during which employees of a car wash in Yangzhou, Jiangsu province, received a 2 RMB lottery ticket apiece instead of a promised 500 RMB cash prize.

Hu opined that humorous gifts are acceptable if employers make it clear ahead of time that there would be less cash bonus available due to financial or other constraints, instead of setting high expectations and failing to meet them. “Who would want to work for such an employer?”

For now, the workers lugging home crates of cooking oil and rice can only envy their compatriots at Chinese tech giants, which compete to give their employees the most generous gifts each year: E-commerce firm Alibaba, for example, gives an extra month’s worth of wages plus cash gifts and company shares, with a total value equal to seven months of an employee’s salary on average. Phone-maker Huawei is set to give out 2 billion RMB in bonuses this year, averaging eight months’ salary for each employee.

Then again, the tech sector is also infamous for a culture of frequent and poorly remunerated overtime work. Truly, there is no such thing as a free lunch—not even a box of chocolates.

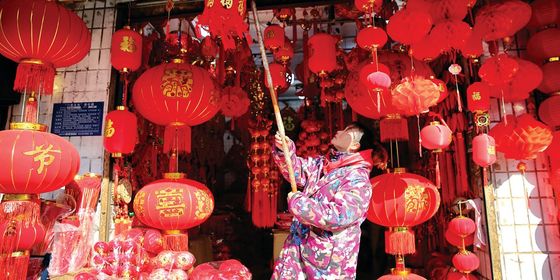

Cover photo by Brian Jeffery Beggerly from Flickr