The Palace Museum gives an inside look on how emperors celebrated the lunar new year

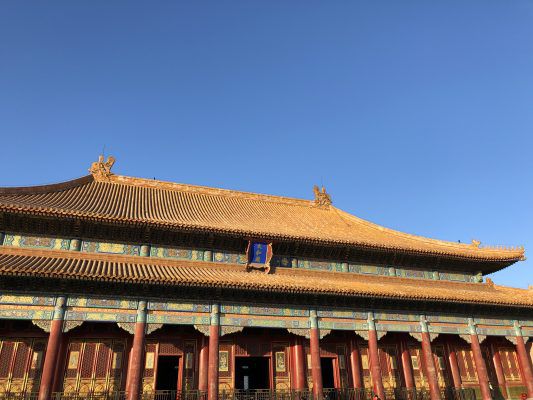

It was a crisp, blue-skied Sunday in January when TWOC visited the Forbidden City for a new exhibition about imperial Spring Festival traditions.

Nearby, the National Museum is still advertising its “40 Years of Reform and Opening up” exhibition, but our destination was much more historical, even if the admission process was thoroughly modern.

Long gone are the hour-long lines of yore: a visit to the Palace Museum today means pre-purchasing tickets online and scanning the e-ticket for expedited entrance. (If the 80,000-person daily admissions quota has not been reached, tickets can also be purchased at the door.)

Thanks to a plethora of television drama, fascination with imperial culture has seen a revival in recent years. Expect to see bevies of young women, dressed in dynastic clothing taking part in impromptu photo shoots.

Recognizing this, the museum has become increasingly savvy about promoting China’s imperial past. Not only has the Palace Museum’s shop become hugely popular (with satellite shops, including at the China World Mall), the Forbidden City also recently opened up a chic coffee shop in the northwest corner, garnering instant fame on social media. (We cannot comment on the coffee’s taste, preferring to forgo the one-hour wait to get inside the shop.)

The Palace Museum has been reaching out to younger audiences

Considering the Palace Museum is securely in the realm of the ancient, the exhibition is geared towards China’s tech-savvy young. Imperial paintings of emperors during the Spring Festival are animated on massive screens, with the objects portrayed, and their descriptions, situated alongside.

Paintings come to life at the new exhibition, such as this one of the Qianlong emperor

Many replicas on display are also immortalized in paintings of the imperial family

While it is stuffed to the brim with priceless artifacts and ornate craftsmanship, the exhibition also provides a human perspective on China’s “sons of heaven,” including their wishes for continued prosperity; fear of evil spirits; and the desire for healthy wives and children.

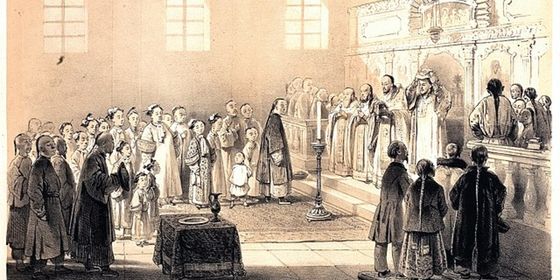

Of course, the emperors didn’t celebrate Lunar New Year like the rest of China. They had orchestras chime and gong in the year (the instruments are on display); they went to ice skating shows with acrobatics; and they had to eat certain meals while wearing certain clothes (while the food is no longer is with us, the clothes certainly are).

One highlight are replicas of original Spring Festival lanterns, displayed throughout

Although the exhibition is beautiful, there is not much English. Regardless, the entire exhibition is social-media friendly (including giant reproductions of paintings that you can literally step into)—so even if you don’t understand everything, you can take some beautiful photos. Be sure to check it out before it ends in early April.

The author poses in front of a giant replica of an imperial painting

Photos courtesy of Ai Tian