From the last emperor’s autobiography to the reminisces of Lang Lang and Mao’s bodyguard, here are some of TWOC’s favorite memoirs

From Emperor to Citizen: the Autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Puyi – Aisin-Gioro Puyi

First published in Chinese in 1964 at the encouragement of Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, this autobiography was the inspiration of the 1987 biopic The Last Emperor. The memoir takes Aisin-Gioro Puyi through many culture shocks and emotional upheavals in his eventful life: Become emperor of China at age 2, losing the empire at age 5, serving as emperor of the Japanese puppet state in Manchuria, undergoing complete re-education under the Communists, and, finally, leading a life as an ordinary citizen. The account ends with Puyi’s release from prison—pardoned by the Communist Party—and becoming a gardener and then a researcher of literary and historical materials.

Although the final product is predictably imbued with a servile tone towards the Maoist regime, the ghostwriter interviewed Puyi to add color to what was originally a wooden self-critique written by the former emperor in prison, and the final product is a fascinating account of a man whose life was intertwined with three distinct periods of modern Chinese history.

Mao Zedong: Man, Not God – Li Yinqiao and Quan Yanchi

Translated to English by the Foreign Languages Press in 1992, Mao Zedong: Man, Not God is dictated by Li Yinqiao, Mao’s former bodyguard, to writer Quan Yanchi. Covering the end of World War II through civil war with the Nationalists and the early ears of the PRC, the memoir providing valuable insights into the leader’s private life, as well as some funny anecdotes: For instance, while watching a Peking opera, Mao Zedong loosened his pants to relax; then, he became inflamed at the feudalistic antagonist that he stood up to give an impromptu speech—and his pants came off. Li noted that Mao treated him almost like a son, and in return, he made sure that Mao’s crates of books were transported safely as they fled Nationalist forces and would ensured the entire compound was quiet during Mao’s odd sleeping hours. While doubtlessly a deliberately sympathetic portrayal, especially compared to Li Zhishui’s The Private Life of Chairman Mao, this book marks a change in Mao’s portrayal: not as a deity but a man with flaws.

A Journey of a Thousand Miles: My Story – Lang Lang and David Ritz

Before he was a famous pianist performing at concert halls around the world, Lang Lang was a little boy with a “tiger father.” The Cultural Revolution—which thwarted both his parents’ musical aspirations—the one-child policy ensured that the whole family’s musical dreams were put in their only son. Before Lang was 10 years old, his father had quit his job as a policeman and relocated with him to Beijing for his musical career (leaving his mother in their native Shenyang to work to support the family). Lang describes his relationship with music as that of both solace and pressure: He recounts how he once tried to destroy his hands, reportedly after he was dismissed by his teacher and his father instructed him to commit suicide. Co-written with David Ritz, Journey of a Thousand Miles is is the story of passion, suffering, and sacrifice behind the career of a talented classical musician.

A Single Tear – Wu Ningkun

“I came. I suffered. I survived”—Chinese scholar and translator Wu Ningkun thus summarizes his turbulent life in China after he quit his doctoral studies in the US and returned to “build” new China in the 1950s. In his memoir, Wu details his experiences with persecution from the “Three Antis Campaign” in 1951 to the 10-year Cultural Revolution. Readers can learn the life of a typical Chinese scholar in the chaos of those years.

First published by Atlantic Monthly Press in 1993, the book was translated and published in Chinese by Taiwan Asian Culture publishing house in 2007. However, neither version is available in Chinese mainland.

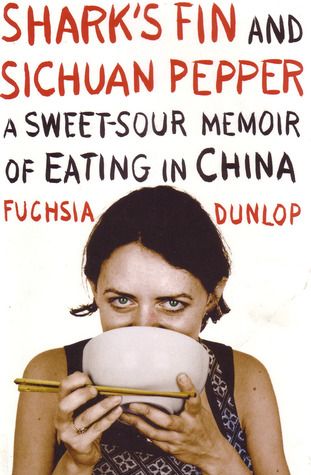

Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper: a sweet-sour memoir of eating in China – Fuchsia Dunlop

Your mileage may vary on this one: As the first westerner to train at the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine, Fuchsia Dunlop arrives in Chengdu in 1994 and vows that she’ll eat anything she’s offered, no matter how “alien” or “bizarre.” Thus begins a cross-country culinary adventure that interweaves tales of food preparation with anecdotes about friends that Dunlop meets in China. If you can get past the fish-out-of-water cliches—the trepidation of a white woman going to China alone, the morbid fascination with butchery, the supposed adventurousness of trying foods that a billion people already eat—there are mouthwatering descriptions of the diversity of Chinese food cultures and rather thoughtful meditations on how food is embedded in regional identities and cultural memories.