Usurper, emperor, hard worker: The short and paranoid reign of the Yongzheng Emperor of the Qing

On December 20, 1722, the Kangxi Emperor, ruler of the Qing Empire for over six decades, died in his villa at the Old Summer Palace outside of Beijing. At his side was Prince Yinzhen (胤禛), his fourth son.

Yinzhen had just arrived after spending most of the week preparing to serve in his father’s place at the imperial sacrifices held each Winter Solstice at the Temple of Heaven. These sacrifices to Heaven re-established the legitimacy of the ruling dynasty, and Yinzhen relished acting as his father’s understudy for such a role, hoping it would be a stepping stone to his own imperial future.

The Kangxi Emperor had accomplished many things in his 60 years on the throne—ending rebellions, conquering new territories, consolidating Manchu rule over China—but naming a successor was not one of them. In a remarkable edict in 1717, when he was close to 70, he wrote of having over 150 sons, grandsons, and great-grandsons.

The emperor’s first choice for heir apparent had been his second son, Yinreng (胤礽), whom he designated as crown prince in 1675, when Yinreng was just an infant. But the young prince grew into a troubled young man who exhibited signs of mental instability, exacerbated by the stress of knowing that many of his brothers jealously plotted against him. The emperor finally deposed Yinreng as crown prince in 1712 and never publicly named a replacement.

“Now, officials have memorialized, requesting that I set up an heir apparent to share duties with me—that’s because they feared my life might end abruptly,” the emperor lamented in his 1717 edict, which was translated by Pei-kai Cheng, Michael Lestz, and Jonathan Spence in The Search for Modern China. “For the last ten years, I’ve been writing out (and keeping sealed) what I intend to do and what my feelings are, though I haven’t finished yet. Appointing the heir-apparent is a great matter; how could I neglect it?”

The choice was never going to be easy. Twenty-four of the emperor’s sons survived into adulthood. By the time of Yinreng’s fall from grace, nine princes were vying for their father’s throne.

Yinzhen was a strong contender. His father routinely consulted him on state matters, and he had shown himself to be a capable and hardworking administrator, if sometimes overly severe. But was he the favorite?

Yinzhen’s main rival was his brother, Yinti, the 14th Prince. Yinzhen and Yinti (胤禵) shared a special bond—and the same mother—but ultimately found themselves in opposing factions at court. Yinti had the support of many of his half-siblings, who regarded Yinzhen as aloof, stern, and cold. Yinzhen relied upon his connections with powerful officials and trusted members of the imperial clan.

Stories of how Yinzhen ultimately succeeded in taking power almost immediately became fodder for centuries of court whispers, palace rumors, and Beijing back-alley gossip, not to mention myriad telenovelas. Did Yinzhen poison his father? Did somebody tamper with the Kangxi Emperor’s final will?

More likely, Yinzhen’s success was due to his being in Beijing as the situation unfolded. At the time of their father’s death, Yinti was thousands of kilometers away, overseeing a military campaign to pacify the western regions. Just to be sure, Yinzhen also placed one of his close allies, the Han bannerman Nian Gengyao (年羹尧), in Yinti’s camp to keep an eye on the younger brother.

Yinzhen also had the support of an influential member of the extended imperial family: Longkodo, the brother-in-law (as well as a cousin) of the Kangxi Emperor. As Guardian of the Nine Gates, Longkodo controlled the imperial guards and the city watch, and it was Longkodo’s men who escorted, with swords at the ready, the body of the Kangxi Emperor—and the grieving Fourth Prince—back to the Forbidden City in the crucial days following the emperor’s death.

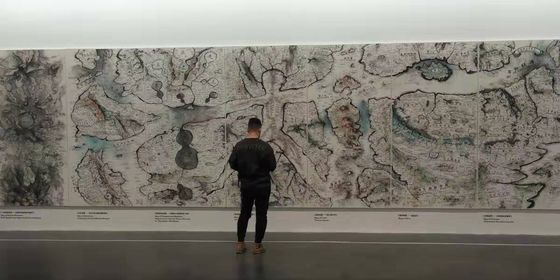

The Yongzheng Emperor’s legacy is often forgotten compared to that of his long-reigning father and son (VCG)

The full story of Yinzhen’s ascension may never be known. The contest for succession did not end with Yinzhen’s coronation but continued on as an information war. As the Yongzheng Emperor, Yinzhen attacked his political rivals, imprisoning many of his own brothers—including Yinti—and executing their supporters. Yinzhen’s partisans also removed any evidence that might taint the emperor’s claim to the throne, with imperial publishing projects, court histories, and document collections.

Not that Yinzhen was a bad ruler: Known to history as the Yongzheng Emperor, he was renowned for his incredible work ethic, often laboring from four in the morning until long into the night reading documents, meeting with officials, and writing letters.

As emperor, he pushed through a series of fiscal and administrative reforms that put the empire on a sound financial footing, and improved government efficiency. He had little time for the hunting parties and southern sojourns enjoyed by his father or, later, his heir, the Qianlong Emperor.

Here too, Yinzhen left his mark on dynastic politics. Aware of his father’s angst over the issue of succession, and no doubt sensitive to the optics of an orderly transfer of power, Yinzhen created the institution of the “Heir Apparent Box.” Under this system, the emperor would secretly write the name of his chosen heir in an edict that would then be locked in a special box placed up high in the Palace of Heavenly Purity in the Inner Court of the Forbidden City. Never again, Yinzhen hoped, would there need to be questions and quarrels over who would sit on the Dragon throne.

Yinzhen reigned from 1722 until his death in 1735. While his time on the throne was not nearly as long as his father or son, who both ruled for 60 years, the energy with which the Yongzheng Emperor approached his job was unmatched in the annals of Qing history. It is entirely possible that he read more, wrote more, and personally handled a greater number of decisions and matters of state in his 13 years than his son did in over six decades.

But despite Yinzhen’s best efforts and a tireless work ethic, he could never escape his greatest fear: That the calumnies of usurpation would be his lasting legacy.

Cover image from VCG