Three traditional celebrations worthy of being better remembered

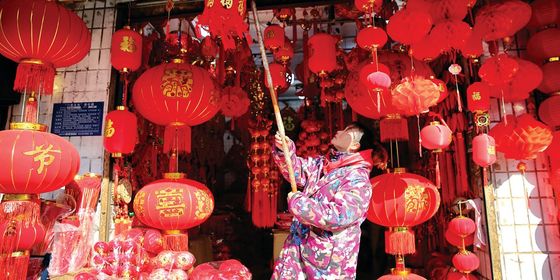

The ultimate Chinese festival tradition is, undoubtedly, the Spring Festival or Chinese New Year, where people travel up to thousands of kilometers to visit their families, cook vast banquets, distribute “red packets,” and set off firecrackers.

However, China has hundreds of other ancient festivals that, although largely ignored by the authorities, are still celebrated by some today. Modernity may have exerted pressure on China’s folk traditions, but ancient festivals celebrating hungry ghosts, winter clothing, cold food, and the god of water, have clung on in part.

Though some of the following celebrations are diminished in recent years, they contain the cultural traditions that underpin much of Chinese culture and society, even today:

Renri Festival (人日节)

Nüwa is the creator of humanity in Chinese mythology

Celebrated on the seventh day of the first lunar month, Renri is considered the day that human beings were created by the goddess Nüwa (女娲) in ancient Chinese mythology. According to Dongfang Shuo’s (东方朔) Book on Divination《占书》, written during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), on the first day of the first lunar month, Nüwa created chickens, and then from the second to the sixth day added dogs, pigs, sheep, ox, horses; finally, on the seventh day, she created humans.

The festival appears to have existed since at least the Jin Dynasty (266 – 420), and people would celebrate by wearing rensheng (人胜) or caisheng (彩胜), a human-shaped head adornment made of silk, colored paper, and gold and silver leaves. The celebrations were most vigorous during the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907), when emperors personally gave rensheng to their subjects and would hold lavish banquets for officials at the imperial court. Folk tradition also holds that if the weather is good and the sun shines on the Renri Festival, it would be a prosperous and fertile year.

Nowadays, some still celebrate the festival as part of Chinese New Year, typically by making a “soup of seven treasures (七宝羹)” with seven fresh seasonal vegetables like leek (韭菜), leaf mustard (芥菜), and celery (芹菜). Some also take the opportunity to think about their own health, perhaps by climbing mountains or checking in on their fitness goals.

Sheri Festival (社日节)

The Kitchen God report’s the family’s good behavior and misdeeds to the Jade Emperor

The festival was established to make sacrifices to the Kitchen God (灶神). It’s said that the two radicals of the character “社,” 示 (altar) and 土 (earth), represent making requests of the Kitchen God.

The festival was celebrated during the fifth wuri (戊日) after the Start of Spring (立春). In Daoist chronology, every 60 days is a one calendar cycle, and every six days within it is called a wuri. Earth, or “土,” is the fifth Daoist element after water, fire, wood, and metal (水火木金). Consequently, the Kitchen God is honored on the fifth wuri of spring.

On this day, a ceremony named chunqi qiubao (春祈秋报), literally meaning “pray in the spring and make sacrifices in the autumn” to the Kitchen God, was traditionally performed. The spring part of the ritual was created in the Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256BCE), before the autumn rituals were added during the Han.

Lovers took the festival for their own, and a tradition of dating on this day emerged. As the ancient text The Rites of Zhou《周礼》states, “On this day in the middle of the spring, lovers go out to woo without restrictions (仲春之月,令会男女,于是时也,奔者不禁).” Somewhat alarmingly, the perfect spot for a rendezvous was said to be a mulberry forest surrounding a sacrificial altar. Mulberries were said to embody the sun (阳, yang), the male representation in Daoist thought, while the sacrificial site represented the female moon (阴, yin). The combination of yin and yang was said to make all under heaven prosperous.

Huazhao Festival (花朝节)

Today, revelers often dress up for flower watching during the Huazhao Festival

This festival of flowers is celebrated on the 15th day of the second lunar month, and dates at least as far back as the Southern Song (1127-1279).

Revelers traveled around the capital Lin’an (now Hangzhou) in search of the best flower-watching spots, often bringing a piece of paper and a writing brush for composing poems. Many also brought a shovel and a basket for picking wild herbs like Shepherd’s Purse, and copper coins for buying seasonal delicacies.

Lin’an’s West Lake would be crowded, with the many flower markets lining the banks filled with customers. After picking wild herbs and buying flowers at the market, people could sample “hundred flowers wine (百花酒)” and “hundred flowers cakes (百花糕).” After that, they could visit the theater to watch operas, dances, and even cuju (an ancient Chinese form of soccer).

This festival was also one of the few days in the year when young women were free to go out in public, thus young males attended flower viewings to search for a potential bride. As the women admired the flowers, they could catch the eye of many young lads.

All images from VCG