“Rap of China” hopeful on why she refuses to conform in an increasingly stifled hip-hop industry

“China doesn’t understand rap…[it’s like] pearls before swine; claims 28-year-old rapper Xie Qin, who goes by her stage name Mila. “They just don’t know how to appreciate it,”

Mila was one of thousands of contestants eliminated from The Rap of China, the hit iQiyi streaming platform, before the first episode had even aired. In its second season, the American Idol-style contest is now known by its new name 《中国新说唱》 (China’s New Rap).

In one recent episode, celebrity judge Kris Wu told contestant Al Rocco that his dream was to “spread Chinese hip-hop around the world.” The realities of the music industry, though, fall short of Wu’s dreams—to say nothing of the dreams of artists who rely on shows like The Rap of China to transform a passion into a career, especially one independent from increasingly commercialized labels—not to mention the oppressive monitoring of the censors.

Mila’s views on the industry are pessimistic. “Countless managers have offered me their full support and guaranteed fame in exchange for sexual favors. It’s a very dark market; nobody actually cares how good you are.”

It’s not just sour grapes: Last summer, Mila’s road to stardom seemed guaranteed. Having signed an eight-year contract with Rongyi Media, a Beijing-based company, the jiulinghou rapper was promised myriad opportunities to perform in live concerts around Beijing, and advertorials in the press.

For a while, this seemed the right choice. Growing up in small-town Sichuan, Mila says she was rebellious from a young age, skipping class in her teens, and singing in bars and clubs. Her parents, though, gave her a lot of freedom and respected her choices. She fell in love with Western pop while listening to the likes of Britney Spears, Mariah Carey, and Snoop Dogg. After coming to Beijing to start her career, a Ukrainian boyfriend converted her to rap.

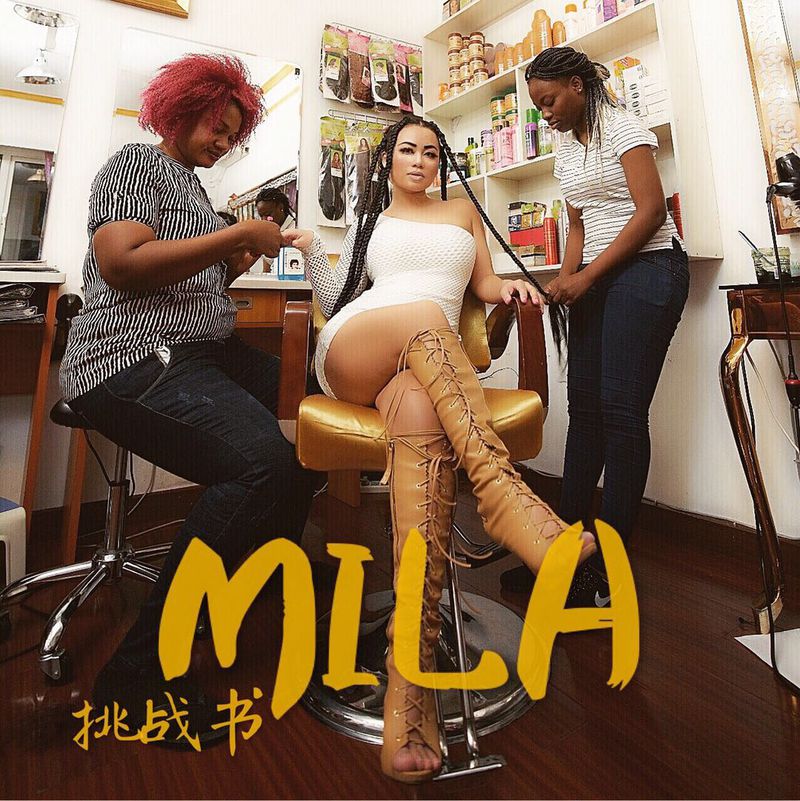

I met Mila, at an African hairdresser in Sanlitun in October, shortly after she signed with Rongyi; she was getting dreads done while doing a photoshoot for her single, self-titled “Mila.”

The resulting album cover. Mila says the title 挑战书 “Letter of Challenge”, is aimed at the industry’s plethora of “fake” rappers (image courtesy of Mila)

A few weeks later, she invited me to participate in her live-stream show, which her label requires every signed artist to perform two hours a day, six days a week. Despite the popularity of live streaming, Mila explained that hers was “closed”—the stream was only available on an internal platform, viewed by a few hundred company employees. When Rongyi deemed her ready for the big stages, they would aggressively promote her on Chinese social media.

Although there was no set date for when this would happen, Rongyi had one advantage that Mila felt would be crucial: The company had a record of success producing under increasingly strict government regulations over online content and the arts, and promised that their artists would become “the face of Beijing and, by extension, the country’s whole music scene,” as she recalls.

However, Mila’s career prospects took a turn for the worse. In late December, PG One, co-winner of the first season of Rap of China, became involved in an affair with married actress Li Xiaolu. In the public fallout of the scandal, the government issue a notice in January that labeled hip-hop culture as one of several “subversive” subcultures—along with tattoos and sang culture—as unfit for television.

Afterwards, Mila says, Rongyi encouraged her to take on a patriotic mantle. In February, she released a song and MV with American producer Joshua King, titled “I Love China.”

The song’s celebration of all things Chinese, in addition to the music video’s setting on the Great Wall, is similar to a better known patriotic rap song, “The Great Wall”, released in June by PG One’s less controversial co-champion GAI. Both are consistent with a broader trend among state-affiliated media to attempt more stylish and modern “popaganda” for the millennial market.

By March, though, Rongyi had stopped organizing performances for Mila to showcase her rap, deciding instead that her live-streaming skills could be put to use hosting a talk show that the company would promote. Meanwhile, other artists had either left the label or been forced to change their styles, which many were willing to do; after all, Rongyi’s contract came with a comfortable salary, excellent health insurance, and education subsidies for the artist’s children.

Mila, though, was less interested in financial security than using Rongyi’s resources to help her own style of rap “go mainstream.” Now ready to resign from the company, she is on the lookout for other labels, as well as opportunities to promote her music on her own, including via The Rap of China.

In May, Mila spent a week sending all of her WeChat contacts the link to a voting platform for The Rap of China, where her name was ranked alongside thousands of other aspiring rappers in the Beijing area in a competitive ballot system, where only the top 20 rappers could advance to the actual show. Without corporate backing, though, amassing enough votes was almost impossible. Mila gave up trying after two weeks, and instead joined the millions of spectators who tune in to the show every weekend—though she is somewhat more opinionated about both the judges and participants than most regular viewers.

Mila on the Rap of China–Beijing ballot. By May 26, she had received 1,836 votes, and was ranked 138th (image from Mila’s WeChat)

“Rap of China is all about money. If you want to make it onto the TV show, you need money, or at least someone willing to sponsor you,” she explained as the new season aired. “People in China like songs they can sing along to, but that’s pop, not hip-hop.” To illustrate, she played a sample song sent by a producer—one of many interested in signing her, she claims, none of whose definition of “rap” is acceptable to her. The clip contains a lot of guitar-strumming, boy-band singing, and four verses of rap in the middle.

Mila characterizes her own style as guojihua (国际化,“internationalized”). She raps in Chinese, but has Western musical influences. She hopes to find a foreign producer in Beijing with enough Chinese-language skills to be able to find venues, create contacts, and run a label—a practically inexistent combination. The size of her Chinese fan base doesn’t seem to bother her, either; with China’s growing economic and soft power, she believes her guojihua style will have its day—and will, in fact, “raise the general standard” of rap in China.

In the meantime, Mila tries to stay true to her roots, consistently and even aggressively challenging mainstream conventions with her music as well as her appearance. She is proud of her voluptuous body, which, she argues, proves that “Chinese girls can also have a big ass and boobs.” On sunny days, she tans by the pool rather than protect herself with an umbrella, like many young Chinese women, and greets friends with a hug and two kisses.

“This road I’ve chosen is hard, but no regrets,” Mila says, taking a long drag from a hookah, a favorite way of de-stressing from her stalled career for the past few months. I ask why she doesn’t just drop her niche and tailor her rap to Chinese audiences. “Because rapping like Nicky Minaj, not Jay Chou, is who I am. Fame and money can’t change that.”

Update, July 31, 2018: Mila announced at 5 p.m. today that she has resigned from Rongyi, and is planning to start working with two foreign producers, with the long-term aim of creating a music label together.