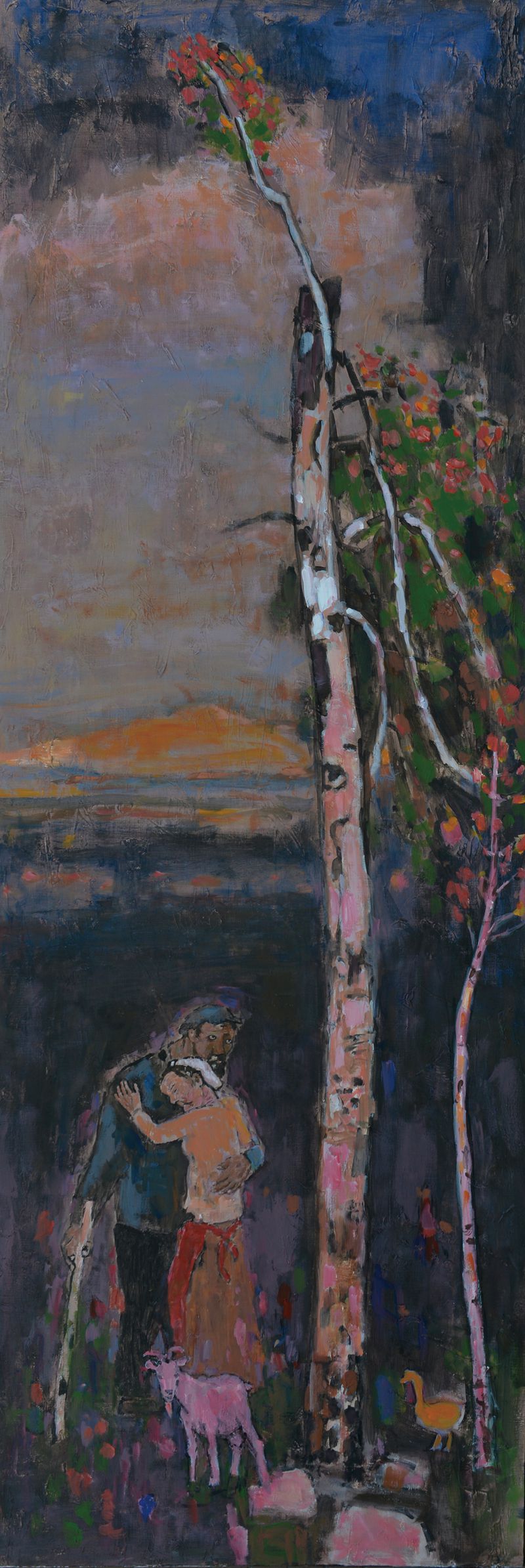

Artist Wang Zhanwu paints a love letter to a small northern community

Six years ago, a winter landscape in Inner Mongolia inspired Wang Zhanwu to write “The Village of Aouni,” a narrative poem of a man who sends many letters to a woman he loves, until he returns to a small farm in the Great Khingan Mountains and finds her standing at the door.

This October, the poet and artist from Heilongjiang province opened his solo exhibition “A Letter to the Village of Aouni” in Beijing’s 798 Art District, exhibiting oil paintings inspired by the romance of the poem. Under Wang’s riotous palette, small villages, mysterious women, and lifelike animals bring alive the personal emotions behind his work, which he shares with TWOC:

“The Village of Aouni” series, 2020

What is the connection between the poem and the paintings?

One night, when I was traveling in Inner Mongolia, I suddenly felt something, maybe inspiration from my past experiences, so I wrote the poem, and shed tears after finishing it. I sent it to my friends, and they all felt very touched, and asked me if this really happened. I told them that “Aouni” is not based on a certain experience from my life, but the sum of the experiences of my whole life. Picasso said that “art is a lie that tells the truth,” so “The Village of Aouni” is the truest lie. It does not exist, but there is a forest farm called Aouni in the Great Khingan Mountains, where I collected inspiration. In Aouni there is everything I want to pursue; there is such a woman waiting in the entryway of everyone’s heart, who is waiting for us to look back. Later, I started to create this group of paintings. The process was really unstructured and it took six years.

“Thousand Miles Away,” 2012

The village scenes look typical of northeastern China, where you were born. How did your upbringing influence your art?

I was born in northern China, and my grandmother is from Mongolia. I have a profound respect for the Inner Mongolian nomadic people. When I was creating this group of paintings, I went to Inner Mongolia many times for inspiration. The horse in my work “Thousand Miles Away” is the most important spiritual totem of nomadic peoples. It can be said that my paintings are full of spirituality and wildness. When people evaluate a painter’s work, they often use adjectives like “simple,” heavy,” and “light.” The most commonly used word for my paintings is “spiritual.” This may also have something to do with my art studies in Guangzhou, an open-minded city. My university experience allowed me to develop an unfettered creative style.

“The Village of Aouni” series, 2020

What do poetry and painting mean to you?

Writing poems is not my job. I write poems as a hobby and due to creative instinct. I also like to listen to music. I don’t think artists should be separated into categories. Literature, music, and paintings all have beginnings, climaxes, and endings. Just as painting uses different tones, music also has tones. The colors of a painting make up the picture, and musical tones make up the melody; all of this is closely connected.

After decades of creating art, what do you see as your artistic mission?

My mission is to explore the “infinite psychological space.” Contemporary art has many forms of expression. Artists try to innovate with external forms, but I believe that the foundation of art is emotion. It is more important to find the spiritual core of creation than to pursue innovation on the outside. I can always experience a baptism of my heart when I paint. I think I’m seeking for my soul in my paintings. When we expand the outer boundaries of art, we set boundaries for ourselves, but the dimensions of our hearts and emotions are infinite; what you get is a vast, endless world.

“The Village of Aouni” series, 2020

All images by Gallery 798 ICI LABAS

Soul’s Entryway is a story from our issue, “Rural Rising.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.