Elderly Chinese are moving abroad to join family, but their journeys are far from smooth

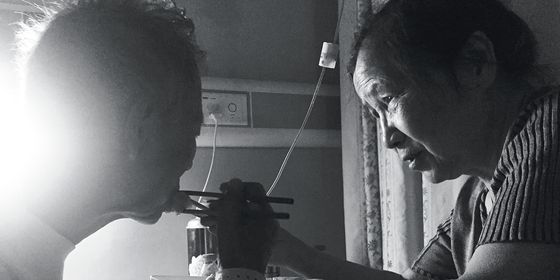

Migrating abroad is among the toughest challenges a person can face in life. For young people, in the prime of their lives and careers, it’s daunting. For elderly people with little experience of foreign countries, it can be downright terrifying.

Fortunately, most don’t need to make the move alone. By far the most common scenario in which elderly people in China move abroad is to be with family members who have already emigrated. Although they have family in their new homes, they still face myriad daily challenges when adapting to their new lives.

“Many of them are uprooted from their established social network in China, so they feel stuck at home and isolated even though they live with their children’s family. Some of them try to go out but because of their unfamiliarity with the community and neighborhood, and because of culture and language barriers, they don’t feel safe going around,” said Dr. Josephine Fong, program director for youth and family services at Canada’s Centre for Immigrant & Community Services (CICS).

“Unlike China, Canada is a country with a lot of land but a small population, so they can be walking around their neighborhood for hours during the day without seeing anyone on the street, because the adults are at work and the children are at school.”

CICS is one of a number of community organizations around the world that offer assistance to new migrants, such as language classes, in order to help them adapt to the new community. CICS has a number of activities that encourage these seniors to build a social network, such as cooking and gardening classes, as well as lessons on using iPads and computers. They also offer classes on issues related to paying taxes and avoiding scams.

Scams are just one potential problem that senior Chinese migrants might encounter abroad. Closer to home, strained ties with family are another difficulty. “If they have inconsiderate children, the elderly may feel that they are being used as lived-in nannies, childminders, household caretakers or maids, and so on; all for free services, yet without any gesture of appreciation,” Dr. Fong pointed out.

Chinese media regularly run headlines on the most popular foreign destinations for emigrants each year, with Canada and Australia often given top billing. This doesn’t necessarily mean they’re actually the top destinations in terms of numbers though. The most recent statistics in the OECD’s international migration database are for 2014, and Korea tops the list for Chinese migrants with 192,000. Japan comes second with 98,000. Then the US follows with around 76,000, the UK with 39,000 and Australia and Canada with 27,000 and 24,000 respectively.

These figures are for foreign population inflows, however, and can’t represent the myriad degrees of belonging that migrants may experience, whether it’s in formal measures like permanent residency or citizenship, or their personal sense of belonging. The local political atmosphere is another consideration, with migration frequently in the headlines, particularly during election seasons. In late 2016, Australia’s productivity commission released a report into parliament, indicating that around 8,700 parents of naturalized citizens come into the country every year, with healthcare and other costs for each annual group adding up to around 3.2 billion AUD over the course of a lifetime. The report generated some media attention, but was largely overshadowed by controversies relating to refugees—another hot-button migration issue.

For the migrants themselves, before even setting foot overseas, the process must begin in China. TWOC spoke with a Ms. Li, from Jiangsu province, who has a daughter in the process of applying for a marriage visa in Australia. If successful, one day, Li may move.

“If I didn’t have any family overseas I wouldn’t want to move. At my age it would be really hard to fit in. But with a child there it would be like a buffer, a medium to get used to Western society. Chinese people, of all people, need their children’s help when they get old, because we don’t have the facilities to help elderly in our society.”

“My retirement salary is already pretty good in my area,” she said. “I can live comfortably here so far. However, If my [daughter] is overseas, I have no other choice but to move to whichever city she’s going to move to, so at least I will have someone to send me to the hospital in emergencies.”

She said that while a desire to move to a more developed country is common, it is far from universal among her peers. “Some Chinese friends of mine wouldn’t want to move overseas even if they could, because they can’t stand being lonely. They want to stay with their mahjong friends in the environment that they’re familiar with because they’re scared of learning new things. I can stand being lonely, I guess.”

She was optimistic she could learn some “basic English.” “Language is going to be a problem at first of course,” she said. “But in some countries there will be lots of Chinese people in some communities. And given a language environment we will be forced to learn. It depends on the person. Some people learn faster than others.”

Most of Li’s reasons for choosing to emigrate, aside from being with family, relate to problems in China. “I have a college friend who married an American guy in the 1990s and they had three children. All are very cute and outgoing, unlike Chinese kids whose spirits are crushed by homework. If I had three kids, none of them would have been able to afford college, let alone graduate school.”

Li spends a lot of time online, and also chatting with friends, so TWOC asked her what her impressions she has formed of the “best” country to move to. “America, Canada, Northern Europe, Australia and maybe New Zealand?” she said. “America is good, but the gun problem is serious. Canada is too cold, and I don’t like cold environments. Northern Europe is harder to immigrate to, and despite the good welfare, it’s also too cold and there aren’t existing Chinese communities. Australia and New Zealand have better climates, my daughter told me.”

Despite the worries, there are, of course, plenty of happy stories. Dr. Fong pointed out that the most important advice she can give for migrants seeking a happy life overseas is to create a community of friends. “It’s important for them to have peers who can understand their needs, inner doubts or struggles, play with them at their physical level, laugh with them for things that are familiar to their generation, and to have some professional support and guidance when they are troubled socially and emotionally.”

“After all,” she said, “only when seniors can have their own life that they won’t be perceived as ‘a burden’ to their grown-up children and they don’t have to ‘rely’ so much on their children to keep them happy.”

Migration After Middle Age is a story from our issue, “Wildest Fantasy.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.