On the remote margins of the East China Sea, a fishing community has been rediscovered as a “post-90s” travel paradise

On evenings when the East China Sea is balmy and stirred to the right consistency by a passing storm, a chemical process causes the micro-plankton off Huaniao Island (花鸟岛) to glow like tiny blue beacons on the tide. Chinese travel writers sometimes call this the “fluorescent sea” (荧光海) or, if feeling creative, “the blue tears of the ocean.” Locals don’t have a name for it.

“We used to just say, ‘Hey look! The night sea is criminally bright (贼亮 zéiliàng)!’” says Ms. Ye, a middle-aged shopkeeper on the island. “Young people came and told us, ‘this is fluorescent sea.’ None of us are much educated—those who don’t do business with young people, like me, probably still don’t know!”

Huaniao, literally “Flower Bird” Island, sits at the northernmost point of this windblown archipelago of around 400 isles known as the Shengsi Islands (嵊泗列岛). It’s geographically closer to Shanghai than the city that actually governs it—Zhoushan, Zhejiang province—but in practical terms, it’s miles from nowhere.

Just 35 nautical miles from international waters, Huaniao and its surrounding isles are favorite destinations for tourists who journey at least 24 hours to be the first in China to catch the sunrise. But the islands’ inconvenience and isolation is already causing native residents to migrate—most iconically in the case of Houtouwan village on Shengsi’s easternmost island, which has been visited by numerous news crews in the decade since being abandoned and picturesquely reclaimed by the vines.

But for younger holidaymakers, it’s like rediscovering an Eden. On WeChat moments, travelogues on Mafengwo.com, and live-stream channels, Huaniao emerges as 360 degrees of sun-kissed coastline and postcard views. There are no cars on the island, so its only road is always blissfully empty, an artfully winding backdrop against which almost every tourist will pose, hair purposefully tousled and arms splayed open.

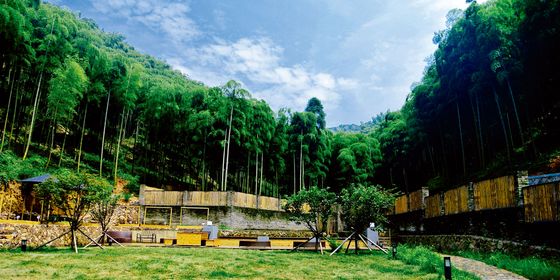

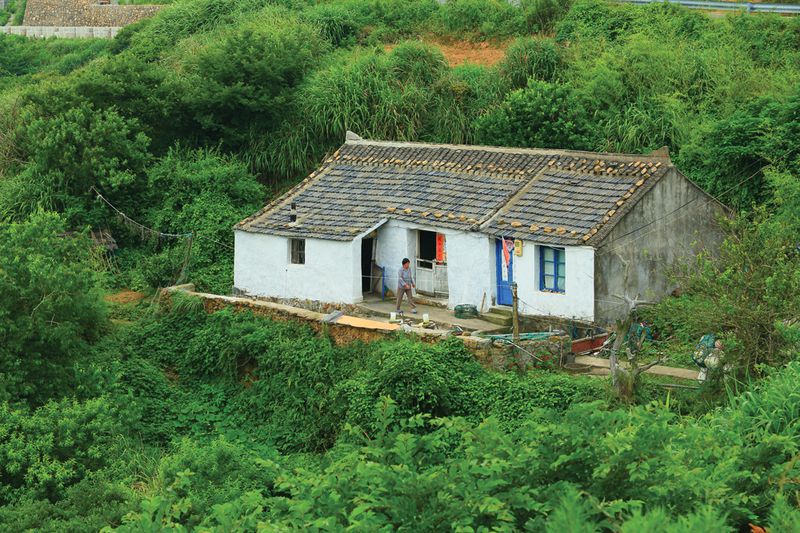

On the far side of the island, away from tourist development, Lighthouse village preserves Huaniao’s original architecture and fishing economy (VCG)

The mise-en-scène is completed by occasional wildflowers, a harbor of gently bobbing boats, and the cluster of whitewashed, blue-trimmed buildings—repainted in a deliberate attempt to mimic the Greek island of Santorini—in the larger of the island’s two fishing villages. In the world’s most populous country, letting everyone know you’re far from the madding crowd is half the point of the journey.

As Ms. Ye tells it, the island is starving for young people. Yet the phalanxes of backpackers doing the circuit of whimsically-named sights—a 147-year-old lighthouse, the ruins of Huaniao’s own abandoned village, mountain caves, and two boulders named “Mandarin’s Hat” and “Buddha’s Hand”—are not exactly the end-goal for officials in charge of developing tourism on the island. “They want the island’s own young people to return, from Shengsi [“base island”], from Shanghai, where they’ve gone to look for jobs or more interesting things to do. They want them to see that it’s a lucrative place to set up a tourism business, so they’ll come back and open up guesthouses,” says Chen, my host and owner of Misty Island Charm guesthouse, above the island’s South Beach.

Chen, who is in his 30s, came back to the island with his wife, a Huaniao native, to start the business soon after they’d married. A decade later, their story is still almost unique.

Instead, the guesthouse trade is dominated by a group that locals refer to as “those six places”—establishments started over the past three years by young mainland visitors who become so enraptured by the place that they decided to stay. Wang Yuewei, the first of the six to arrive back in 2014, says it was easy to get a 10-year lease on one of the many houses left empty by owners who’d left the island. All that remained was to fix them up according to the tastes of travelers from his own “post-90s” generation: Quirky murals, Scandinavian furniture, shelves of nautical-themed knickknacks and postcards and books.

“It’s an ideal toward living,” Wang says, explaining why he stayed. “You start with the ideal—‘I want to live by the sea’—and then you find something that lets you make a living while you do it.” Yet in the off-season when the sea churns, the air is foggy, and the backpackers stay away, he and other young hoteliers also shut up their houses and leave, wintering on the mainland in cities like Ningbo and Shanghai, or abroad, where they become adventurers cataloguing the exotic places of the world.

Visitors came to Huaniao for stunning sea views and a sense of seclusion (VCG)

It’s May 1, Labor Day, the official end of the October-April fishing season in the East China Sea. This afternoon, in the lull before the start of the tourist season in late May, Mr. Ying has the waterfront practically to himself. Sitting in a brightly painted skiff parked on the beach, he stares into the distance and talks of fish.

“Twenty, 30 years ago, you could cast a net and you couldn’t pull it back up because it’s full of fish,” he reminisces. “You’d sail out to sea and they’d come up to here—” he knocks on the side of his boat to illustrate—“but there is very little fish now.”

On Huaniao, the sea has long been the reason for everything. According to Ms. Ye, some of the island’s early settlers, including her ancestors, had been bandits and coastal pirates fleeing justice on the mainland; the treacherous waters kept them safe from the law and supplied them with food and occasional shipwreck plunder. In 1870, the British built Huaniao Lighthouse at a strategic route from the Pacific to their new treaty ports in the Yangtze River. At 16.5 meters tall, it remains the island’s only landmark of note, powering up at dusk year-round to illuminate what’s still one of the busiest shipping routes in the world.

In the present day, the sea is often a source of isolation and inconvenience, brought on by its dwindling prospects as a means of subsistence. Of all the world’s major bodies of water, the East China Sea suffers most from the effects of overfishing, according to Chinese Ministry of Agriculture. The Shengsi archipelago has had a negative population growth since 1998. According to the 2011 census, more than 60 percent of residents in Shengsi county are over 40. The local fishermen assure me that I’ll never see another mariner under that age, that the younger generations have no ability or, indeed, interest in fishing—and why should they, if it’s hard work that pays so poorly?

Boats moored off the beach of Shengsi’s base island are a picturesque backdrop for photo-takers, occasionally taking visitors on fishing trips (VCG)

Huaniao has just shy of 1,000 full-time residents across two villages, not counting a small military base on the island, and there’s not a child in either community, except those who come to see their elderly relatives during school holidays—the island’s only school, a primary school, closed down in 2015. It has since become a nursing home.

Running errands off any of Shengsi’s outlying islands is a multi-day project. From Huaniao, it’s two hours’ boat ride to Shengsi’s base island, the only place where one can collect parcels, shop for food, see a doctor, or catch another ferry to Shanghai or Zhoushan. Periodic gales can shut down all crossings for days at a time. Residents budget at least one night’s stay each time they leave their island and often wait for serious symptoms to appear before they’ll make the trip to the base island’s sole hospital.

In the fishing season their routine remains stubbornly old-fashioned, with men setting out to sea each calm day in painted boats, and women doing the heavy-lifting onshore: cleaning, sorting, towing in the lines. In the tourist season, fishing families repair their boats, cast nets, and cook for the young holidaymakers who take up lodgings in their homes. Fresh catches from the sea—the ubiquitous yellow croaker, oysters, the occasional succulent swimmer crab or squid, alongside platefuls of mantis shrimp—are still the island’s calling card in spite of the dwindling ocean stock. The unspecified “vegetable” dish on offer at most family restaurants, on the other hand, refers to whichever vegetable happens to be at hand.

These days when the boats still sail, it’s often for a different reason. I learn that the painted skiffs moored off the pier in Huaniao, as well as the iridescent fleets back on the base island, aren’t just permanently stationed for beachgoers to take photos—they’re waiting to take paying guests out to enjoy a “fishing experience.” For around 200 RMB a head, visitors can keep whatever they catch, which isn’t usually much. But the villages stay in business, and boats take their lines out to see, day in, day out.

Calling itself “the No. 1 Lighthouse of the Far East,” the Huaniao lighthouse still operates year-round (Hatty Liu)

And residents like Mr. Ying get to preserve their way of life. He tells me of his large family—“five brothers, two sisters”—who’d come from generations of fishermen but have almost all left the trade. When I ask about the difficulties of living on the island, he says the biggest challenge is that fish doesn’t fetch as high a price as it did. During off-season, Mr. Ying lays nets around the beach to catch fish and clams to eat.

“So do you ever leave here?” I finally ask.

He thinks for a bit. “Yes, in the fishing season I go out to sea to fish, but that was before; there’s not much fish now.”

I try to change the subject from fish. “What about when you don’t fish? Do you do other things outside the island?”

“Oh, sure I go, I go to lots of places,” Mr. Ying’s face splits into a wide smile. “I’ve been to Ningbo, and Shanghai, to sell my fish.”

Whimsical signposts are part of the island’s youthful makeover (VCG)

A boat is like the clothes you wear. Some people like red, so they wear red. You paint the boat whatever you like, everyone is different,” Mr. Li, an elderly fisherman fixing buoys on the pier, tells me. Like everyone else, he’s been repeating bleak prognostications about the island’s future in fishing, but when I admire the dazzling colors of the boats, he comes alive. “It’s like dressing yourself up to go out; a boat doesn’t look nice when it’s old, so we paint it often so it looks bright.”

It’s an apt summary of the direction tourism is taking in Huaniao. The government seems to have taken cues from “those six places” when marketing to post-90s youths. Besides literally covering everything in a bright coat of paint, a section of the road in the main village is being converted into a main street, lined with window boxes, vintage bicycles, postcard shops, and cafes (none of which are yet open for business).

“Of course you can have a vision, ‘I want this island to develop in such and such a way,’” says Chen. “But it doesn’t just happen like that. [The island] is changing, but one step at a time.” His mother-in-law is more optimistic, citing the example of a neighboring island: “Do you know Dongji Island? They had no people either, then they developed tourism, and suddenly all the people came back!”

“It doesn’t exactly work like that,” Chen tells me apologetically after she leaves. The newfound popularity of Dongji likely has less to do with official directives than its appearance in the 2014 road-trip movie The Continent, the directorial debut of former celebrity blogger Han Han. “Special people, magical land/The first to feel the winds off the sea…/You are paradise on Earth…/And we will never leave” go the lyrics of “Island Anthem,” a song Han Han penned for the film’s soundtrack.

Yellow croakers are the mainstay of dinner tables all over the island (VCG)

The sea continues to bring people to Huaniao: It’s not uncommon to hear tourists grilling locals about which islands to visit, complaining that the waters around Shengsi itself are too close to the Yangtze Delta to shed its brown silt. “Yes, the sea around Gouqi [Island] really is blue,” I overhear a local man patiently explain to a woman by the ticket window. “You can go to Huaniao too. They also have sea there.”

And if the new visitors’ relationship with the sea is shallower than before, it remains enthusiastic. As I flip through the travel albums that Wang and his guests share with me, their carefully curated angles, iridescent filters, and tireless search for flattering expressions and backdrops reminds me of old Mr. Li down at the harbor—like him, they are searching for ways to express an admiration for island life.

That night, we go down to the beach together to see the fluorescent sea, though it’s not yet the ideal season. The whole village is dark, except for the even-tempo sweep of the lighthouse beams; it’s criminally cold. The place seems like any ordinary village in the Chinese countryside, home to left-behind elderly and precarious ways of life. Yet it still has the ability to captivate outsiders. “Look! Look over there,” my companions run across the sand, pointing. “The sea, it’s so bright!”

Leaving next morning, a Category-9 storm begins to form behind us. It will shut down all transportation to Huainiao for the next three days, leaving the questions of its difficult past, changing present, and splendid plans for the future to be settled another time.

Nowhere Land is a story from our issue, “Beyond Go.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.