Why is the internet full of the character 口 (mouth)?

In the past few months, netizens have found the comments sections on social media and “bullet screens” on TV dramas filled with seemingly nonsensical phrases. For example, “What doesn’t mouth me to death only makes me stronger (口不死我的只会让我更强大 Kǒu bù sǐ wǒ de zhǐ huì ràng wǒ gèng qiángdà).” Or another comment that just appears as “Black mouth mouth mouth gone, while the light is eternal (黑口口口过去,光明才是永恒的 Hēi kǒu kǒu kǒu guòqù, guāngmíng cái shì yǒnghéng de).”

Such sentences are not deliberate attempts at gibberish, but a quirk of internet platforms’ censorship regimes. The first example is meant to read “what doesn’t kill me makes me stronger (杀不死我的只会让我更强大 Shā bù sǐ wǒ de zhǐ huì ràng wǒ gèng qiángdà),” but the character 杀 (shā, to kill) has been scrubbed by the social platform as a sensitive term and replaced by a generic box that looks like the character 口 (kǒu, mouth), which can also refer to oral sex. The second example should read, “The dark night will eventually pass, but the light is eternal (黑夜总会过去,光明才是永恒的 Hēiyè zǒng huì guòqù, guāngmíng cái shì yǒnghéng de),” but three boxes have replaced the characters 夜总会 (yèzǒnghuì), which together form the word for “nightclub” (though not in the context of this sentence). This was apparently also flagged as sensitive.

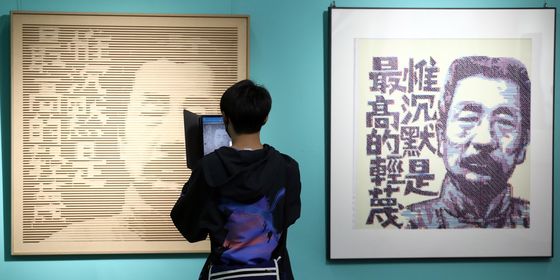

The censors’ (or algorithms’) attempts to redact sensitive terms has led to confusion, but also bred creativity, as netizens have taken to deliberately replacing words with 口 to avoid the censors or for comic effect, a practice that has been dubbed: “Oral Literature (口口文学 Kǒu Kǒu Wénxué).” For example, “A soldier accepts mouth, rather than humiliation (士可口不可辱 Shì kě kǒu bù kě rǔ), replaces the idiom “A soldier accepts death, rather than humiliation (士可杀不可辱 Shì kě shā bù kě rǔ).”

The censorship has descended into farce in some instances. For example, the novel To Kill a Mockingbird (《杀死一只知更鸟》 Shāsǐ Yì Zhī Zhīgēngniǎo) has become “To Blow a Mockingbird to Death (口死一只知更鸟 Kǒusǐ Yì Zhī Zhīgēngniǎo).” While Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill (《杀死比尔》 Shāsǐ Bǐ’ěr) was changed into “Blow Bill (口死比尔 Kǒusǐ Bǐ’ěr).” Netizens quipped: “In the future, the online world will not be bloody, but pornographic (以后的世界没有血腥,都是黄色 Yǐhòu de shìjiè méiyǒu xuèxīng, dōu shì huángsè).”

Some wondered whether internet platforms’ attempts to “harmonize” content online had gone too far when they found the name of Three Kingdoms era (220 – 208) warlord Cao Cao (曹操) showed up as Cao Kou (曹口), since the character 操 (cāo) can also be used as a curse word. One netizen moaned that deciphering comments online had become “An exercise to enhance our fill-in-the-blank skills (这是在锻炼自己完型填空的能力 Zhè shì zài duànliàn zìjǐ wánxíng tiánkòng de nénglì).”

This is not the first time netizens got creative in order to avoid censors, or simply to mock online platforms’ scrubbing of sensitive terms. The word 和谐 (héxié, harmonious), for example, was once often used in official announcements, such as in the phrase 和谐社会 (héxié shèhuì, harmonious society), but also often appears in messages by social media platforms after their online censors block sensitive, pornographic, or violent content. The term was then widely mocked by netizens, who would complain that the content they want to post might get “harmonized (被和谐掉 bèi héxié diào).” But once censors cottoned on to the mocking tone with which netizens used the term, they started removing content with the word 和谐, forcing netizens to replace the word with the phrase “river crab (河蟹 héxiè),” which sounds similar. Now netizens might quip: “Don’t say that, or your comment might get ‘river crabbed’ (别这么说,当心被河蟹掉 Bié zhème shuō, dāngxīn bèi héxiè diào).”

Netizens go to great lengths to avoid being “river crabbed.” They use pinyin, or pinyin abbreviations, to refer to potentially sensitive topics, such as using “zf” for “government (政府 zhèngfǔ).” They may also use a character with the same sound, like 淦 (gàn), a rare character originally referring to water leaking into a boat, to replace 干 (gàn), which can mean “fuck.” Similar-looking characters can work too, like 果 (guǒ, fruit) instead of 裸 (luǒ, naked).

Another way to use words that might get removed is to split a character into its radicals and post them separately. For example, the character 枪 (qiāng, gun) is broken down into the wood radical 木 (mù) on the left and 仓 (cāng), meaning warehouse, on the right.

Inappropriate language on TV shows is often “bleeped” out, and netizens have taken to doing the same thing in their posts by replacing vulgar words with the character 哔 (bì), which sounds like a bleep.

For now, these techniques have helped netizens post their feelings without seeing their comments deleted, and have a laugh too. But last week, microblogging platform Weibo announced it would start cracking down on “inappropriate content” posted using homophones or even emojis—netizens may soon need new techniques to avoid getting caught in the claws of the river crab.