For centuries, Chinese funerals demanded living sacrifices to accompany the dead in the afterlife

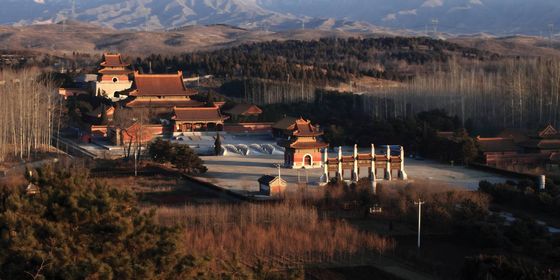

In the burial pits of Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇), first emperor of imperial China and founder of the Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE), in Shaanxi province, next to the nearly 9,000 famous figurines of the terracotta army, archaeologists found something else too: the human remains of thousands buried, likely alive, together with the deceased emperor.

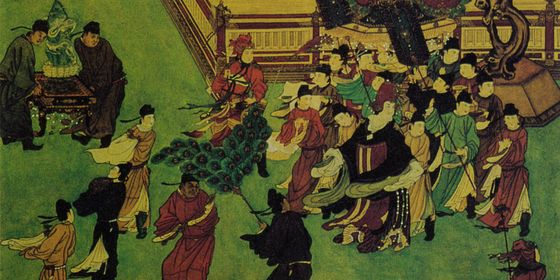

These poor souls died as part of an infamous institution of burying the living along with the dead so they could take care of them in the afterlife, known as xunzang (殉葬 xùnzàng, sacrificial burial) or renxun (人殉 rénxùn, human sacrifice). The practice can be found in most dynasties of imperial China, even up to the most recent, the Qing (1616 – 1911), despite repeated attempts to ban it. Throughout these millennia, it led to thousands of deaths, forced or otherwise.

According to the Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》), a history of ancient China by Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) scholar Sima Qian (司马迁), after Qin Shi Huang died, his son and successor Huhai (胡亥) ordered his soldiers to “execute and bury all [his father’s] concubines who had never given birth,” because “it was inappropriate to let them leave the palace.” Sima didn’t explain exactly how many people died at this order, but recorded that “it was a large number.” At present, of the 99 small tombs archaeologists have discovered inside the mausoleum, 10 have been excavated, and all of them contain the bones of numerous young women.

Thousands of construction workers who built the magnificent mausoleum to the famously tyrannical ruler also became victims. Sima recorded that after Qin Shi Huang’s burial was complete, someone pointed out that the construction workers might reveal what they knew of the inner workings of the mausoleum, which contained vast treasures and was booby-trapped to the teeth to protect it from grave robbers.

Huhai’s solution was to close the gates of the mausoleum after the funeral ended, trapping all the workers inside. Historical records show that about 720,000 people worked on the mausoleum. Even if not all of them were killed, it’s reasonable to believe the death toll was terribly high.

Qin Shi Huang was not the first ruler, nor the last, to have a funeral complete with xunzang. The practice is most famously associated with the Shang dynasty (1600 – 1046 BCE). At the Mausoleum of Late Shang Kings at Houjiazhuang in Yinxu (in present-day Henan province), believed to be the last capital of the Shang dynasty, researchers found 164 skeletons in the burial pits, probably killed to keep the dead kings company in the afterlife.