South Koreans are the biggest group of international students in China, but all is not harmonious on campus

At nightfall, young couples flock to Peking University (PKU)’s Nameless Lake, seeking privacy amid the dense foliage and dim light.

But occasionally, tribal-like chanting breaks the peaceful silence, startling the lovebirds out of their tryst.

“Gonbae! Aja! Aja! Aja!” roar a group of Korean international students, taking turns to goad one another into downing shot after shot of soju (Korean rice liquor).

Ever since South Korea and China established diplomatic relations in 1992, Korean students have constituted the largest group of international students at China’s top universities. According to a study by Inside Higher Ed, Korean students accounted for 30 percent of all overseas students at China’s first-tier universities in 2008; in 2012, this figure had risen to 70 percent.

Over the past few years, Chinese students and professors have vented their frustrations at this omnipresent group, with varying degrees of vitriol. A question posted last October on Zhihu, China’s largest Q & A platform, asking Chinese students their opinion of Korean students, has already received 555 replies.

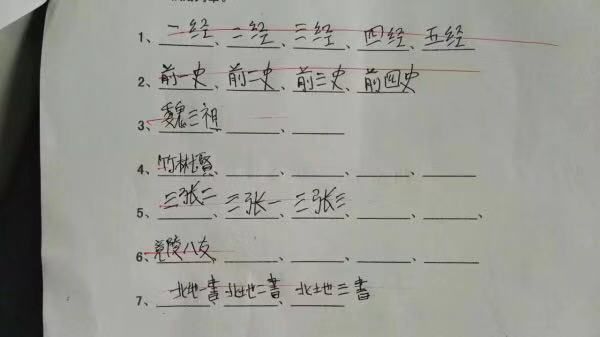

The three most “liked” replies are revealing: a Peking University teaching assistant, posting a screenshot of a plagiarized essay by a Korean student; a Zhejiang University alumnus’s picture of a Korean student’s Ancient Chinese exam paper that received zero marks; and a Tsinghua University student’s story of a Korean student who incited a brawl after kicking a ball into a Chinese student’s head, then refusing to apologize.

Exam paper of a Korean student on Zhihu, in which the students wrote joke or placeholder answers to avoid submitting a blank exam (Zhihu)

“I remember being put in a group with two Korean students once,” says Wang Junxia, a journalism undergraduate at PKU. “When the time came for everyone to submit their part of the group presentation, we couldn’t reach them; the teacher said they asked for sick leave. [I heard] they did that again to another group next semester, and got away with it by claiming they were depressed.”

The “outsider” status of Korean students in Chinese universities is not surprising in itself; a similar phenomenon has been noted of Chinese students in American or British universities. But the countless accounts of lazy, misbehaving students is in stark contrast with stereotypes about Korean students in the US, who are often portrayed as GPA-obsessed library rats.

Experts say that differences in the way South Koreans perceive the US and China influence their approach to study-abroad opportunities. There is a widespread perception among Korean youth of China as a dirt-poor country; a few years ago, an internet meme satirized Korean tourists visiting China, becoming astounded by its level of development, and exclaiming, “Civilization!” upon seeing innovations such as QR code-scanning.

Aside from ingrained prejudices, feelings of disenchantment also play a role. Joseph Lee, a 32-year-old Korean PhD candidate in Beijing, claims that the vast majority of Korean international students will have attempted (and failed) to get into one of their own top universities, known as “SKY”: Seoul National University, Korea University, and Yonsei University. Their second choice, after taking a year out to prepare their application, would be an Ivy League university; only after being rejected by these do they settle for China.

Those who are unsuccessful breaking into the SKY trifecta see China as an alternative way of gaining the upper hand in a hyper-competitive job market that has led South Korean youth to call their country “Hell Korea.” After all, South Korea’s biggest trading partner is China, which means hundreds of companies are looking to hire bilingual employees every year.

“It is the dream of every Korean student in China to go to the US,” Lee alleges. After completing his undergraduate studies in the US, Lee landed a job in South Korea’s Ministry of Unification. After working there for five years, he decided to pursue a doctorate at PKU in order to improve his chances of working on both US and China-related policy projects.

“There is a clear hierarchy in the recruiting process for jobs like mine: US, SKY, China,” Lee tells TWOC.

According to 52-year old Chen Li, a PKU Chinese-language teacher, Korean students are subject to an unhealthy amount of societal pressure that hinders the development of their skills. Chen says that, as the number of Koreans taking the “China route” increases, so does the level of Chinese necessary to stand out from the pool.

This makes mastering Chinese an unbearable source of stress, killing motivation and the patience necessary to achieve an advanced level. This drives students to resort to plagiarism and fake certificates, hoping their diploma alone will be enough to convince employers.

The specter of this negative image follows even hard-working and competent Koreans across their academic career. “When I first approached my PhD supervisor, I didn’t tell him my nationality,” 26-year old Woo Hyun-Gyeong tells TWOC.

In August, Woo obtained the highest score in the entry examination for PKU’s PhD International Relations program, beating dozens of Chinese students along the way. This should have automatically conferred the prestigious faculty scholarship on Woo, but the award committee snubbed her, explaining that the previous 10 awardees had all been Korean, which discouraged talented students from less-developed countries from applying to the program.

“Because there are so many Korean undergraduates who mess around, this gives a bad reputation to the hard-working Master’s and PhD candidates like me,” says Woo, who adds that Korean students at the postgraduate level are doted on by their Chinese supervisors for being exceptionally diligent.

“I really hope things change,” Woo sighs. “You have no idea how many times I’ve had to talk Chinese students out of beating up a drunk Korean friend.”