Glory, profit, talent, literature, and an assassination

In 1897, a 26-year-old typesetter named Xia Ruifang angrily quit his job in at the North China Herald, an English newspaper in Shanghai, because he felt mistreated by his British supervisor. Together with three of his friends, they opened a small printing workshop in a local alley.

Nobody could have expected that this small workshop would then become one of the most famous names in the publishing industry and influence the publishing history of the nation. Such are the origins of TWOC’s publisher, Commercial Press, which is celebrating its 120th anniversary this Friday.

Born in a poor family, Xia wasn’t well-educated. Before he started his career in Shanghai’s fledgling printing industry, he held many kinds of jobs including hospital worker and policeman. In the early days, Commercial Press just had a few simple pieces of equipment and very limited manpower. They had no editorial office and their main business was just printing ads, flyers, and bills commissioned by local businesses. Xia was the manager, proofreader, buyer, and accountant at the same time; he would fetch new supplies of paper and collect debts from clients in person, and even moonlighted as a door-to-door insurance salesman to supplement their income.

Image of Xia Ruifang [ybk168.com]

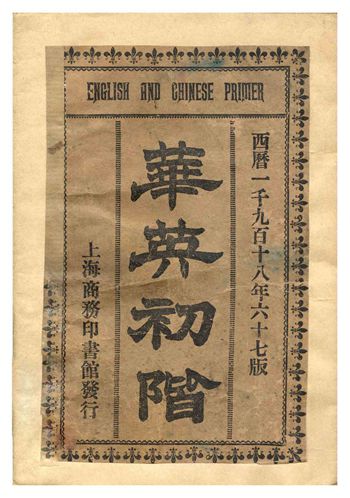

The first big success came along a year after the company was thought up by Xia and his friends. Though Xia couldn’t speak any English, he was acutely aware of an opportunity in the market to publish books teaching English. So, Commercial Press translated and published an English textbook called The Primer, which was designed by the British to teach English to primary school students in India, and named this new work the English and Chinese Primer. This Chinese-English textbook sold 3,000 copies in its first week and enabled Commercial Press to buy advanced printing machines from Japan to open their own printing premises on Dechang Lane in Shanghai’s International Concession.

The 67th version of “English and Chinese Primer”, published in 1918 [igenshan.com]

Xia knew that if Commercial Press wanted to develop well, his own hard work was not enough. He needed help from intellectuals. In 1902, Xia decided to invite Zhang Yuanji to join his company. Zhang used to be a high-ranking official in the Qing Dynasty, but was permanently ousted from the government for his pro-reform proposals. Before meeting Xia, Zhang was working at an unrewarding job at Nanyang College in the city. But Xia valued his talent, and offered him a salary more than three times higher than his previous income. This proved to be the right decision. The formula for the success of Commercial Press, which was set up with a progressive attitude toward both traditional Chinese and Western learning, was fully realized by the joining of forces between Zhang, a jinshi of the old examination system with knowledge of Chinese literature, and Xia, the foreign missionary-educated tradesman who was well-connected in the International Concession and knew the rules of doing business there.

Zhang himself was an outstanding publisher and manger. He recruited many talented individuals for the company and took charge of publishing a large number of high-quality books in the later years. These individuals shared the common goal of educating the whole population of China and made the Commercial Press become one of the most influential publishing organizations in China’s modern history. Sadly, Xia himself was assassinated at the relatively young age of 43, and the assassin was never found.

Timeline of the development of Commercial Press:

In 1902, Zhang began to publish magazines, starting with Diplomatic News.

In 1903, it became China’s first publishers of primary education textbooks. Japanese investors were also invited to join the company.

In 1904, Zhang began collecting books to start Hanfenlou, Commercial Press’s editorial reference library. He also founded another magazine called The Eastern Miscellany.

In 1907, the press moved to a 320,000 square meter new plant.

In 1910, The Eastern Miscellany reached a national circulation of 15,000, becoming the most widely circulated journal in the country. The journal would last until 1948, a record for periodicals published in the Republic of China.

1914 was a momentous year for Commercial Press. Xia attempted to buy out his Japanese investors. But four days later, he was assassinated. There was much speculation as to who was behind the assassination, but no one was ever arrested for the crime.

But the Commercial Press didn’t stop. In the same year, it set up a branch in Hong Kong Museum and also launched the Students’ Magazine.

In 1915, Commercial Press printed it first dictionary, the product that it is probably most well known for today.

In 1916, it set up a branch in Singapore.

In 1924, it opened the Commercial Press Oriental Library.

In 1932, the press had to face new adversity. During the Shanghai Incident, Commercial Press was bombed by the Japanese army, which destroyed its headquarters in Zhabei, Shanghai, as well as the attached Oriental Library and its collection of tens of thousands of rare books. Many of its most influential magazines also stopped publishing after this event.

In 1954, Commercial Press’s headquarters were moved from Shanghai to Beijing, and their focus shifted to academic works published in the West.

In 1993, the separate Commercial Press companies in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia established a joint venture to become Commercial Press International, Limited.

In 2006, The World of Chinese was founded.

In 2011, the Beijing office was changed into a limited liability company. China Publishing and Media Holdings Co., Ltd. was also founded in 2011 and became Commercial Press’s parent company.

After weathering many storms, Commercial Press’s commitment to the Chinese publishing industry has never changed. Chinese publishing history is full of its footprint over the 120 years. Here’s to another century of great achievements。

Cover Image from The Commercial Press (who else?)