Diplomatic translation is never easy, but the task is all the more challenging when established protocols begin to fray

When diplomats from China and the United States met in Alaska for the first high-level bilateral talks of the Biden administration, few expected the translators to steal the spotlight. In China, Zhang Jing won praise for her calm and fluent translation of the Chinese representatives’ remarks, while Zhang’s American counterpart was criticized for amplifying the U.S. delegation’s already strident language.

The famous Chinese comparativist writer Qian Zhongshu once cited an Italian proverb to describe the work of a translator: traduttore traditore—“translator, traitor.” And it’s true: The wording chosen by a translator is always more or less “traitorous” to the original, but Qian wasn’t entirely fair in his assessment. Many linguistic betrayals are often the result of a translator’s loyalty, if not to the language used, then to established diplomatic protocols and speech. Take Zhang, for example. Tasked with translating a catchphrase used by one of the Chinese representatives—“We Chinese Aren’t Buying It!”—she chose to paraphrase, translating it as “This is not the way to deal with the Chinese people.” These adjustments become exponentially more fraught, however, in times of geopolitical upheaval.

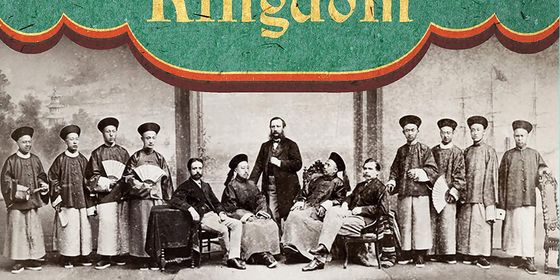

Looking back at the history of Sino-international diplomatic relations, there’s a long tradition of “loyal betrayals.” For example, the famous Macartney Mission to China in 1793 was defined by the supposedly arrogant reply of the Qianlong Emperor to King George III’s entreaties to establish formal diplomatic relations. The resulting diplomatic snafu is frequently cited as evidence of the Qing dynasty’s self-imposed isolation. But Lawrence Wang-Chi Wong, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, has argued that how Qianlong replied may have boiled down to decisions made, not by any diplomat, but by the man who translated King George III’s letter of state: likely José Bernardo de Almeida, a Jesuit priest living in Beijing.