Some anti-marriage activists are trying to lay claim to the self-comb legacy. They’re missing these women’s real significance.

This story was originally published on Sixth Tone and has been republished with permission as part of our collaboration with Sixth Tone X, a platform featuring stories from respected Chinese media outlets.

In my mother’s memories, my great-great-aunt was a stoic, formidable woman of 5-foot-2. The eldest child of an impoverished south China family in the 1890s, all five of her siblings died in childhood. She and her cousin—my great-grandfather—supported each other after their parents died, taking turns working and putting each other through school. Although she never married or had children of her own, after moving in with my great-grandfather and his family, she became the family matriarch, ruling over the household and all her nieces and nephews.

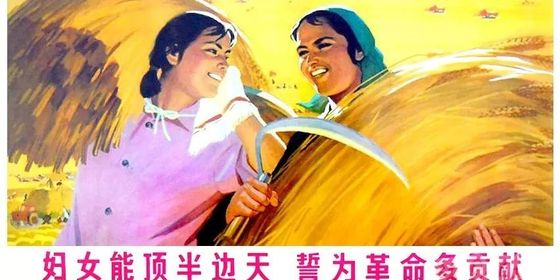

In my hometown of Panyu—once a fishing town, now an affluent district of the southern city of Guangzhou—people like my great-great-aunt used to be known as “self-comb women.” Traditionally, when women got married, they would ceremonially comb their hair into a bun, signifying they were no longer a maiden. Eventually, a mirror ritual evolved for women who opted out of marriage: A self-comb woman would shuqi, or brush her hair up, and perform other rituals associated with matrimony, such as worshipping at an ancestral shrine, gifting sweets to a younger brother, and hosting a celebratory feast. Only, instead of swearing her life to a man, she swore it to herself.

Young women in south China chose to self-comb for a variety of reasons. Some did so out of personal preference, unwilling to submit to the restrictions of married life. Others were pressured by their families, often because older sisters were traditionally expected to marry or self-comb before a younger brother could be wedded.

But for many more, it was primarily an economic decision. The 19th century saw the emergence of a booming silk industry around the Pearl River Delta, and nimble hands were required to harvest silkworm cocoons—or later, to operate new spinning machines. This created financial incentives for families to retain their daughters rather than marry them off.