Beijing’s future economic plans leave little room for the itinerant and low-paid

It’s going to be a long, confusing 40 days.

As part of a safety campaign launched after a deadly fire in Daxing district on November 18, in the past ten days, thousands of low-income residents of Beijing’s illegally built or group-leased housing were (denied by authorities to have been) expelled from their homes en masse, might have received temporary housing or train tickets to their home towns, could possibly have be victims of hasty evictions by some leaders in some villages, may be offered a reprieve until the year’s end…and definitely highlighted a long-simmering debate on the cost and benefit of migrant labor to Beijing.

How much does a city lose from losing its migrant population? The destruction of low-income families’ homes and businesses has invited outrage from a humanitarian standpoint, with more than 100 Chinese intellectuals signing an open letter to the authorities criticizing, among everything, Beijingers’ “ungrateful, arrogant, prejudiced, and shameful repayment unto the nation’s people, especially those at the lowest levels of society.” Much of the ire has focused on media and some policymakers’ use of the term “low-end population” (低端人口) to describe China’s poorly paid, blue-collar urban workers.

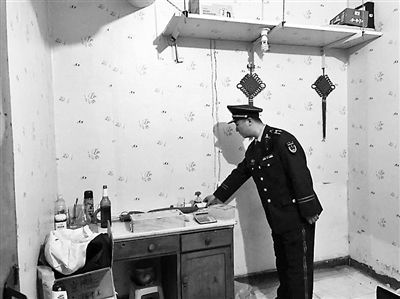

Group-rented basement dwellings and combined commercial-residential units are targeted by the current campaign

This apartment/shop in the Fangzhuang neighborhood fits both descriptions

The term, however, has more complex origins than the prejudice of urbanites, and indicates deeper issues than the need for an attitude adjustment. The actual term came from the concept of a “low-end labor force” (低端劳动力), which has been singled out by the Standing Committee of the Beijing People’s Congress as a key stumbling block to urban development. In a 2010 report, the committee recommended “a mechanism to force the withdrawal of small enterprises and stores that absorb the floating population in large amounts, decreasing [the city’s] demand of the low-end labor force.” The capital’s vision of its future—and China’s as a whole—rests on a consumption-driven economic model, with a skilled service sector, and professional workforce.

Migrant workers are already becoming somewhat negligible in this vision, to a degree. China’s internal migrant population (those who’ve left their original place of hukou registration), stands at 245 million according to the last census; those unable to obtain residency rights in their destination city will be unable to access health, education, and other public services. With the relaxation of residency restrictions and China’s shift to an export-oriented economy in the post-1980s period, millions streamed into factories and construction sites in coastal cities and are credited as drivers of China’s “miraculous” economic performance in this period—but it’s no longer the kind of economic miracle China wants to achieve.

In Beijing, the top sectors for migrant employment tend make the least contribution to its GDP—with the exception of construction. In Haidian district, one of the government’s priority development areas in the IT sector, the wholesale, retail, and food and hospitality sectors combined employ about 60 percent of the district’s migrants but make up 15 percent of its GDP. By contrast, Beijing’s “six high-end industry functional areas”—including the Zhongguancun innovation zone and Xicheng district’s financial zone—contributed to 48.3 percent of the city’s GDP last year and 59.9 percent of its GDP growth over the previous five years, and are identified as priorities in the city’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2016 – 2020).

Migrant laborers’ participation in construction and manufacturing in the city has also decreased in the last decade. According to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, in 2016, 67 percent of long-term Beijing residents from other regions of China were involved in the service sector, with the vast majority employed in “low-end tertiary occupations”—the four biggest being repairs, wholesale and retail, “residential services” (including occupations like housekeeping and security), and hospitality and food. These occupations, identified as the “low end of the service industry chain,” are also some of the lowest paid.

In other aspects, of course, the low end of the chain is indispensable to life in the city: In 2011, based upon experiences of that year’s Spring Festival holiday, Beijing News envisioned a city hit by “housekeeping famine, trash-collection famine, food-service famine” without migrant labor. Skilled workers will need retail and food, and white-collar enterprises can hardly do without cleaning or parcel deliveries—it has been estimated that millions of RMB are lost during the annual Spring Festival alone due to the lull in delivery services. The economic impact of current interruptions to the courier and other sectors are not yet known.

Beijing authorities maintain that they never used the term “low-end population” in any official literature relating to the current safety campaign. In a statement released on the campaign’s sixth day, as the public outcry mounted, the city’s work safety committee emphasized they were simply clearing unsafe structures “where for various reasons the migrant population choose to live and work”: “There is no such thing as a ‘low-end population.’”

However, urbanization policies that increasingly focuses on concentrating high value-added industries and attracting global capital assigns low value to the “low end labor force,” leading to low wages and an increasing gap with a cost of living that’s calibrated to global consumption standards. Residential service and food and hospitality make up two of the three lowest-paid sectors in the city, with workers making less than 50 percent the average salary of the city—and as the wage gap rises, workers increasingly turn to illegal or group-rented properties for housing and commerce.

Policymakers have proposed increased development and improving social services in China’s lower-tier cities or even rural communities as a way out of this trap. Even as, nationwide, China’s factories are moving into the interior, ads have appeared in recently demolished areas touting commercial opportunities in Gaobeidian Economic Development Area, part of a Hebei satellite city 100 kilometers south of Beijing that’s expected to absorb 300,000 of the capital’s population from the agriculture and wholesale sectors.

Resettlement of certain industries and incoming migrants in Hebei is a solution that has been encouraged by Beijing authorities since at least 2010. Eventually, the creation of the Jing-Jin-Ji urban agglomeration will see Hebei communities housing excess population and low value-added industries to support Beijing, a dedicated “political and cultural” capital—the authorities may yet get to have their cake and eat it too.