Hold your breath for one of China’s most underrated goddesses, a murdered concubine who became a patron of toilets and injustices against women

On the 15th night of the Lunar New Year, while some in China go out to enjoy the various festivities surrounding the Lantern Festival, others spend the night on the toilet to take care of important business—not the kind usually spoken about in polite company.

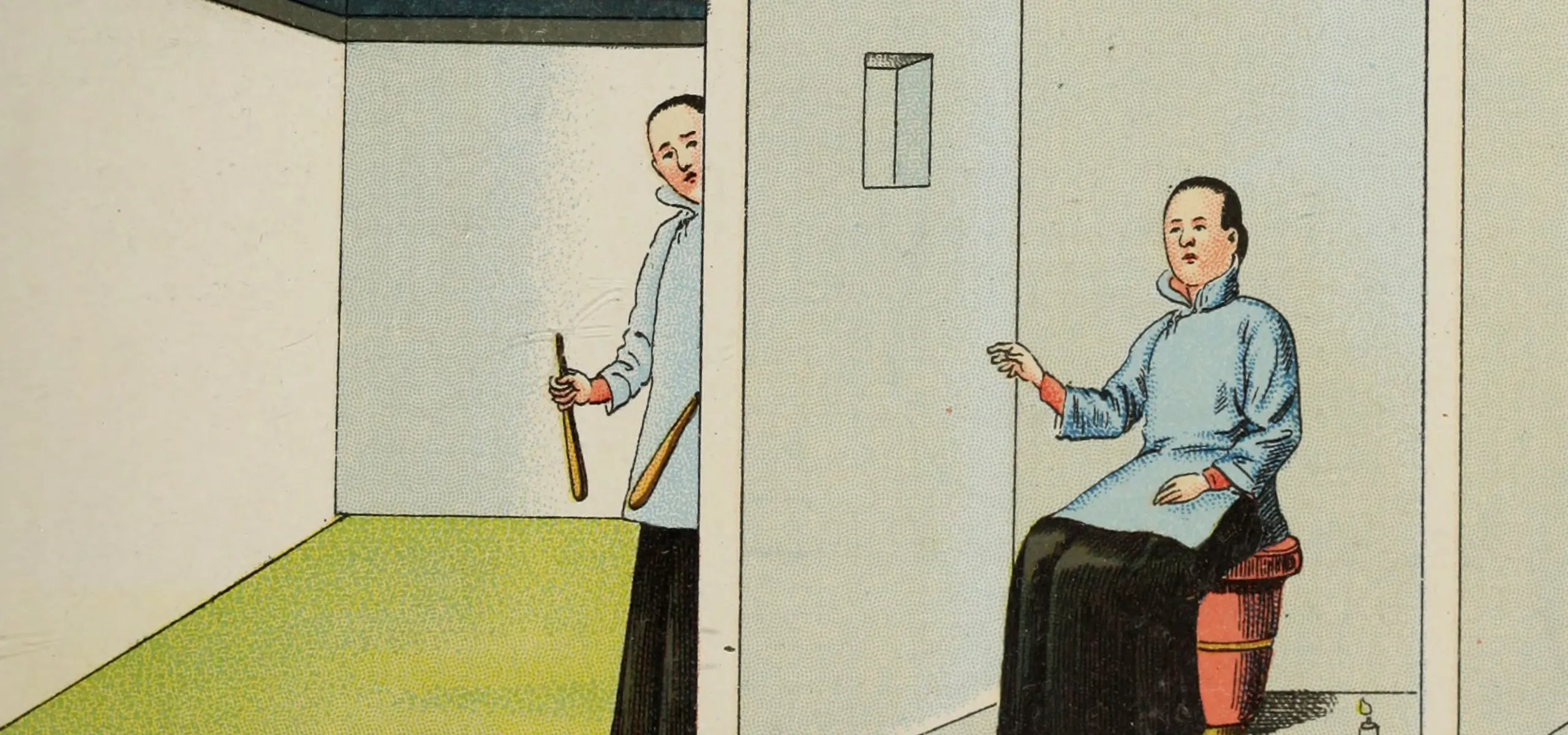

Traditionally, on this night, people clean up their outhouse and perform rituals to welcome an important guest: Zigu (紫姑, “the Purple Lady”), the mysterious toilet goddess who descends to reveal the family’s fortune through spirit writing.

If you were to visit Beijing around this time of year in the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), you might spot women putting paper faces and skirts on hay figurines, making them hosts for the goddess. During the séance-like ritual, after the crowd prays to the goddess with horse dung, drums, and songs, the figurine finally comes alive and gestures to answer questions about the future—as recorded in the Ming book Survey of Scenery and Monuments in the Imperial Capital, which documents Beijing’s urban environment and customs at the time.

From the family farm’s yield, to the silkworms’ health, and the weather of the coming year, people around China, especially rural women, have trusted the toilet goddess’s prophecy on all kinds of domestic matters, as various local historical records indicate. In these records, the dates of worship and names used to address the goddess vary slightly from place to place (including “Third Lady of the Pit” in Shanghai and “Maiden of the Shit Vat” in Ningbo), while she often wrote her verdict (on a bed of rice or dust, or by knocking the table) with a chopstick attached to a woven dustpan.

Nowadays, however, other than in spooky childhood memories, the practice of welcoming Zigu has almost died out. But even though the toilet goddess’s popularity might have been flushed down the drain, her turbulent story has captured many generations’ imagination.