Grow your enthusiasm with the character for growth, length, and seniority

Worried about his crops’ slow growth, a farmer in ancient China figured out a “quick fix”—by pulling them upward. When he came home boasting about his innovation, his son hurried to the field, only to find all the seedlings withered.

This story from Mencius (《孟子》), a Confucian classic consisting of stories and dialogues by philosopher Mencius and his disciples, gave birth to the idiom “pulling up seedlings to help them grow (拔苗助长 bámiáo zhùzhǎng).” The story is now part of Chinese textbooks for elementary students, and the idiom is frequently used to warn people that haste (or excessive enthusiasm) makes waste.

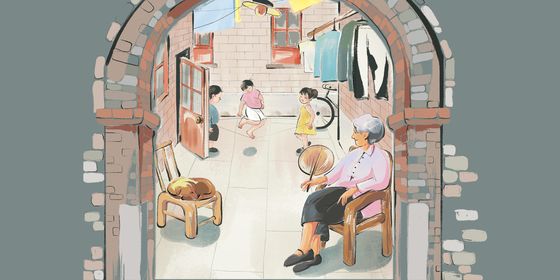

Though Chinese people grew up with such an idea, many fail to take it to heart: For instance, in recent decades, many anxious parents have been criticized for overloading their children with extracurricular courses as early as preschool.

The earliest rendition of the character 长, found in oracle bone script from over 3,000 years ago, looks like a long-haired elder holding a walking stick. One interpretation believes one of the character’s meanings, “long” (including in the sense of length, distance, and time) has to do with the length of the figure’s hair. The character is pronounced cháng when it carries this meaning, as in 长裤 (chángkù, trousers), 长期 (chángqī, long-term), and 长途 (chángtú, long-distance). In the other interpretation, 长’s original form shows its connection to seniority (年长 niánzhǎng) or an elder (长者 zhǎngzhě), associated with the pronunciation zhǎng. While the form of the character was gradually simplified to the current state, the basic meanings have remained.

The Great Wall is 长城 (Chángchéng, ”Long Wall”). Chang’an (长安, today’s Xi’an city of Shaanxi province), the capital of 13 dynasties in ancient China, literally means “long-term political stability.” Often, the idiom 天长地久 (tiāncháng dìjiǔ, “enduring as heaven and earth”) is used to express wishes for everlasting friendship or romantic love.

The character has gradually evolved to mean things that make one stand out (长处 chángchù). Something one is good or skilled at (擅长 shàncháng) becomes their 特长 (tècháng) or 专长 (zhuāncháng). For instance, 儿童文学是她的专长 (Értóng wénxué shì tā de zhuāncháng, children’s literature is her specialty). With the traditional idea that one needs (at least) 一技之长 (yíjìzhīcháng, one skill they excel at) to make a living, Chinese parents have swarmed to enroll their children in extracurricular activities such as painting, piano, and even elite sports like golf, in addition to extra tutoring on academic subjects.

When pronounced zhǎng, 长 takes on a different significance. Traditionally in a Confucian society where 长幼有序 (zhǎngyòu yǒuxù, “there is order for the old and young”), it is important that the young respect their elders. However, there are exceptions: Han Yu (韩愈), a celebrated scholar and educator from the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), writes in his essay “On Teaching (《师说》)”: “Whether a man is noble or lowly, old or young, as long as they can teach me something, they are my teacher (是故无贵无贱,无长无少,道之所存,师之所存也 Shì gù wú guì wú jiàn, wú zhǎng wú shǎo, dào zhī suǒ cún, shī zhī suǒ cún yě).”

The character has then extended to refer to the top of a hierarchy—either the eldest, or someone who holds a leadership position. The first born of a family is 长子 (zhǎngzǐ) or 长女 (zhǎngnǚ). Their siblings can formally address them as 长兄 (zhǎngxiōng, eldest brother) or 长姐 (zhǎngjiě, eldest sister). In traditional big families, the eldest child is often regarded as half a 家长 (jiāzhǎng, parent, literally “family head”), and is expected to take on responsibilities of supporting the family, including taking care of their siblings. Outside the family, a school principal is called 校长 (xiàozhǎng), the chairperson of a company’s board is 董事长 (dǒngshìzhǎng), and a minister is a 部长 (bùzhǎng).

On this basis, 长 has also evolved to indicate growth (生长 shēngzhǎng) and development (成长 chéngzhǎng). Over the last decade or so, Chinese authorities have rolled out many initiatives to enable healthier development of children, such as reducing classwork, curbing after-school tutoring, and piloting “child friendly city” schemes in around 100 cities.

The Daoist sage Zhuangzi (庄子), who lived between the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, once said, “Heaven produces nothing, yet all things are transformed; Earth effects no growth, yet all things are nurtured (天不产而万物化,地不长而万物育 Tiān bù chǎn ér wànwù huà, dì bù zhǎng ér wànwù yù).” Sometimes, letting things develop naturally may be the best choice.

On the Character: 长 is a story from our issue, “Kinder Cities.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.