The seniors’ dance market is a potential gold mine for tech entrepreneurs—but pensioners won’t easily part with their pennies

They’re either health-conscious seniors or public nuisances, depending who you ask. But for years, to many internet entrepreneurs, China’s “square-dancing dama,” middle-aged ladies fond of exercising to ear-piercing music, have represented millions of potential consumers—if only they can figure out how to tap the market.

Found formation dancing in the evening in any reasonably open space—public squares, parks, plazas, even basketball courts and parking lots—all across China, the dama are already known for their economic clout. A 2015 study by Fang Hui, founder of a square-dancing startup, stated that there are 80 to 100 million square dancers and over 2 million square-dance teachers in China. Facing an early retirement age, grown-up single children, and rising disposable incomes, these women developed a reputation for “speculating gold” in 2013, once buying over 300 tons in just 10 days. The close-knit congregations of empty-nesters are also hotbeds for P2P lending schemes, stock-trading, and start-up investment using funds pooled together by dancing troupe—as well as personal finance and health product scams.

These stats have attracted entrepreneurs to make money from the dama market in a more systematic way. Chinese media dubbed 2015 as “The First Year of Square Dance Entrepreneurship.” Since 2015, over 60 apps have been launched targeting those regular square dancers, who usually control the purse strings in their families, according to Beijing Daily.

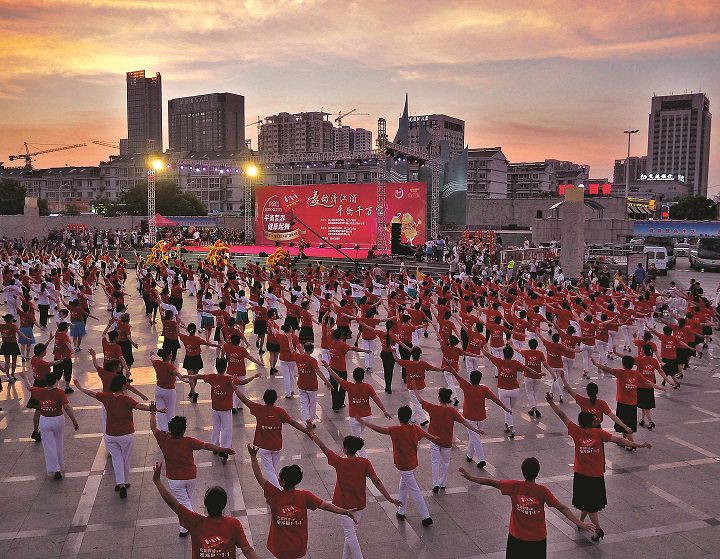

Nearly 1,000 dama dancing in a square in Huai’an, Jiangsu province (VCG)

Cai Rongci, a 58-year-old leading dancer of a Wuhan square-dance group, is a loyal user of these apps. Responsible for teaching moves to over 20 dancers in her group, Cai relies on the videos provided by these apps to learn new choreography. “We have no teachers, but there are so many apps where you can find thousands of dances. I learn first, and then teach others,” says Cai.

However, after a short boom age in 2015, the apps left on the market are not as “many.” In 2017, Beijing Daily reported that most square-dance apps have already shifted target or shut down. “In the past two years, more than 60 square-dance apps have been launched, but now only three or four survive,” claimed the newspaper, “The square dancing dama are still there, but it’s more and more difficult to earn money from them.”

Fan Zhaoyin, who founded the app Jiu Ai Square Dance in 2015, was even less optimistic. “There are only two or three companies left in this market,” he says. Though his own company is doing relatively well, Fan admits that the whole industry is experiencing a reshuffle stage.

In 2012, when Fan Zhaoyin was still working for an internet company, he began to think about starting his own business. By chance, he found that “square dance” was an extremely popular search term on search engine Baidu, gathering 100,000 hits in one day. Thus, he and a few friends founded an online square-dance themed forum, and organized dozens of QQ groups for square-dance lovers to communicate. In less than two years, their registered users reached more than 100,000. By 2015, Fan felt it was time to become a full-time square-dance entrepreneur.

Fan was not the only bull on the square-dancing market at that time. CBNData, in cooperation with Alibaba, released a statistical report in 2015, stating that on average, a square dancer spends 437 RMB on dancing, including 62 RMB for dancing shoes, 90 RMB for outfits, 151 RMB for costumes and 50 RMB for accessories. In Fang Hui’s report, the size of the dancing clothes and loudspeakers market was already estimated at over two billion RMB annually; the health-supplement industry, which also regards the dama as a key market, had reached more than 200 billion RMB annually.

Fang, however, became one of the first victims of the difficulties of conquering this audience. Targeting dama who may need mobile devices to learn dances, Fang and his team founded a company called Dafoo, which developed a tablet especially for elders to use to watch square-dance videos. However, with a price of 699 RMB each, sales of Dafoo tablets were only around 2,000 in total. The project failed just18 months after it started.

Other entrepreneurs tried different approaches. In September 2016, live-streaming platform Youban was launched, aiming to build up a mobile-streaming community for the middle-aged and elderly. Youban provided videos of square dances to attract elderly users, but has seemingly stopped updating since February 2017. Another startup, 99 Square Dance, raised tens of millions in funding from Yingke, a major live-streaming platform, but its live broadcasts ceased in last April as well.

It seems dama’s engagement with these apps and their purchasing power had been seriously overestimated.

Screenshot of Fan’s app, Jiu Ai Square Dance

An interest in square dance doesn’t equate to demand for apps, and other relevant services are even less appealing. “Generally, only leading dancers use these apps; the others just follow us to dance,” says Cai. “For these apps, we only care about if they are convenient or not. As for whether they can make money, we really don’t care.”

Compared with those vanished apps, Fan’s Jiu Ai Square Dance was lucky. Though just one of the only “two or three” surviving players in this industry, Fan says it currently has more than 5 million users. Fan believes the key is more than just accumulating users. “The most important thing is that we have found an effective channel of turning our user traffic into profits,” says he. “Square dance is just an entry point, you can use it to attract users, but should try to make money in other areas.”

By “other areas,” Fan mainly refers to its e-commerce business. Jiu Ai’s in-app and WeChat online stores provide not only square-dance-related commodities but articles of everyday use, including clothes, food, and household items preferred by their user demographic. By now, e-commerce has become the main resource of their revenues, and Fan says the rise of mobile payment is a contributing factor. “Now it’s much easier to teach middle-aged people to use mobile apps or go shopping online. The climate is better than before.”

In fact, before Fan finally found the right way of making money, he also tried a few other directions, such as advertisements for commercial brands and organizing off-line square-dancing competitions, but none worked well enough. “Now we don’t take advertisement anymore, because it’s hard to assure the safety and quality of the brand. We need to protect dama from false advertisements or scams. Once they are deceived, they will leave you,” says Fan. “For us, dama’s trust is the premise and base for everything. We should cultivate trust first, and talk about making money later.”

Paid content is another trend in the internet industry. But Fan doesn’t think it’s the right time for square dance apps to charge for their contents. “It’s exactly these free videos that attract dama, and there are so many free videos online. If you start charging, you are driving them away,” says Fan.

Perhaps Fan is right. For many dama like Cai, square-dance apps are not irreplaceable, and nor are they loyal to one. “We usually just find free content, there are so many apps [that can provide free videos]. And you can also find videos on websites like Tudou or Youku,” says Cai. But Cai doesn’t think it’s impossible for them to pay for content in the future. “If all the apps start charging, it will be OK for me to pay,” says Cai.

On the other hand, though smartphones and mobile apps are increasingly accepted among the middle-aged and the elderly, their enthusiasm for square dance seems to have reached a plateau. Many dama have found alternative ways to exercise. “We don’t dance any more,” says a former dancer surnamed Tian from Liaoning province. “Now we play ping pong or badminton everyday; sometimes we go to kick shuttlecock in the fitness center. It’s more interesting than square dance, and the environment is better.”

Beijing gym-goers practicing yoga (VCG)

Others choose to go to the gym. Wang, a 56-year-old Beijing resident, prefers yoga and belly dance classes at the gym to square dancing. “Exercise in places like a public park? It will be irregular. Working out in a gym, you can have classes at the same time everyday. But if you exercise outside, maybe you just do it once, and never go again,” says Wang.

Fan also agrees that it’s hard to see another boom in dance, but believes it won’t be hard for the square dance market to maintain a certain scale at least for a few years. “Maybe the form of dance will change—like, recently the ‘square shuffle dance’ is very popular. But I don’t think square dance will come to the end in the near future, because old people will continue to work out in the square.”

Cai also has faith in square dance. She claims compared with other ways of exercises, square dance is easier to learn and take part. “It means joy, get-together, and a special landscape of Chinese dama,” Cai says. But just a few days after TWOC’s interview, Cai appeared at a new gym near her home—she’d just bought an 800 RMB trial membership.

Appy Feet is a story from our issue, “Fast Forward.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.