Seven Chinese historical figures who gave up their royal status

British tabloids may have dubbed Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s recent TV interview the “worst royal crisis in 85 years,” but we’re pretty sure China, with 2,000 years of imperial history (and plenty of kings and monarchs before that), has them beat when it comes to royal scandal. In honor of the British couple’s royal exit, let’s take a look at some Chinese royals from history who gave up their exalted status:

Boyi (伯夷) and Shuqi (叔齐)

(VCG)

Boyi and Shuqi were two brothers who lived during the 11th century BCE during the rule of Di Xin (帝辛), the dissipated last ruler of the Shang dynasty (1600 – 1046 BCE). They were the sons of Yawei (亚微), the lord of the vassal Guzhu state. As the eldest son, Boyi was the nominal heir to his father, but Yawei preferred Shuqi. As a filial son, Boyi wanted to respect his father’s wishes and yield the throne, but Shuqi, as a filial younger brother, felt like he couldn’t take it.

Caught in this Confucian catch-22 (500 years before Confucius), the brothers did the only logical thing—flee their home state together. They ended up in Zhou, a vassal state in the west which was recruiting talented people. However, after the Duke of Zhou overthrew the Shang and established his own dynasty, Zhou (1046 – 256 BCE), Boyi and Shuqi protested against this betrayal of their sovereign and vowed they would not eat any food grown in Zhou territory. The brothers retreated to Mount Shouyang (present day Shanxi province) and lived on wild ferns, until they realized that these herbs also technically belonged to Zhou, so they starved themselves to death.

Later scholars, including Confucius and the historian Sima Qian (司马迁), praised Boyi and Shuqi for their strong principles. Their story is also told as an exemplar of love between brothers.

Taibo (泰伯) and Zhongyong (仲雍)

A happier version of Boyi and Shuqi’s story, which appears in the Confucian Classic of Songs as well as Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian, involves the three sons of Duke Tai of the Zhou state: Taibo, Zhongyong, and Liji (季历). Taibo could tell that his father preferred his youngest brother Liji and Liji’s son Ji Chang (姬昌), so he and his second brother Zhongyong fled to the frontier regions of the south, cut their hair, and tattooed themselves to indicate they would no longer compete for the title.

Taibo and Zhongyong settled in present-day Jiangsu province. The locals were impressed by the brothers’ kindness and talent, and submitted to their leadership. During his rule, Taibo developed agriculture in the region and dug the Taibo River, now the Bo River or Bodu River in Wuxi. He died childless, and passed the throne to his brother Zhongyong. Back in Zhou, their nephew Ji Chang and Ji Chang’s son Ji Fa (姬发), the new Dukes of Zhou, overthrew the Shang dynasty and established the Zhou dynasty (and alienated Boyi and Shuqi).

Taibo, also known as Wu Taibo (吴太伯), is still worshiped today as the founder of the Wu state, but the actual dates of his birth and death are unknown and veracity of his story is disputed.

Noble Consort Doulu (豆卢贵妃) of the Tang dynasty

(VCG)

During the reign of the female emperor Wu Zetian (武则天) in the seventh century, a secondary wife of her son Li Dan (李旦), Emperor Ruizong of the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), appears to have left her husband. Noble Consort Doulu became a concubine of Li Dan at 15, and became the foster mother of his son, Li Longji (李隆基), when both the boy’s mother and Li Dan’s primary wife were murdered by Wu Zetian. When she was 44 years old, Consort Doulu’s uncle, Wu Zetian’s chancellor (and distant cousin), submitted a petition to the emperor stating that the Consort missed her family and no longer had affection for her husband, and begged to be allowed to leave Li Dan’s mansion. Wu granted the request.

Not much is known about what exactly spurred Consort Doulu to leave the imperial household, nor about her life after, except that she may have lived in the Renqin neighborhood of the capital Chang’an (now Xi’an) until her death at the age of 79. The consort was all but forgotten by history until archeologists discovered her tomb in 1992 in Luoyang, Henan province, with an inscription telling her remarkable story. She is one of the only known imperial concubines to have “divorced” her spouse. Her foster son Li Longji, later Emperor Xuanzong, appeared to have had fond memories of her and sent ministers and doctors to attend to her before her death.

Wenxiu (文秀)

The only concubine to officially divorce an emperor in Chinese history, Wenxiu became a secondary consort of Puyi (溥仪), the last emperor of the Qing dynasty (1916 – 1911), in 1922. Though Puyi had abdicated in 1912, the imperial household remained in the Forbidden City until the warlord Feng Yuxiang (冯玉祥) expelled them in 1924. They eventually ended up in Tianjin, where Wenxiu wearied of the emptiness of her life and of Puyi’s neglect. She got a divorce in 1931 and was stripped of her imperial titles. She became a schoolteacher in Beijing, married again, and lived in poverty until her death in 1953 at the age of 44.

In his autobiography, Puyi expressed admiration for Wenxiu’s courage: “She received a traditional education and entered the palace at 13, so she had a deep appreciation of monarchy and patriarchy. To request a divorce in that kind of an environment required a double dose of bravery.” Wenxiu was condemned by the public and most of her own family for her decision. In a later chapter, Puyi wrote, “To Wenxiu, there was something more important than status and rites, and that was ordinary family life.” When the descendants of the Qing imperial family petitioned the government to grant Puyi and his consorts to get posthumous titles in 2004, Wenxiu was not included in the request, as she is considered to have become a commoner after divorcing the ex-emperor.

Puyi (溥仪), the last emperor

(VCG)

The last Qing emperor himself “gave up” being royal in a big way, ending over 2,000 years of imperial rule in China when he stepped down from the throne in 1912. The abdication was actually negotiated by Empress Dowager Longyu, since the young emperor was just 6 years old at the time. According to Puyi’s autobiography, From Emperor to Citizen, he was far from happy with this decision and continued to look for ways to regain the throne after he became an adult. He agreed to be enthroned by the Japanese as “emperor” of the puppet state of Manchukuo in China’s northeast in 1934. He was captured by the Soviets in 1945, and was repatriated to China in 1950 after the Communists came to power. Puyi spent 10 years in the Fushun War Criminals Center in Liaoning province, where he underwent “re-education” to become an ordinary citizen: confessing his political crimes, as well as learning basic tasks like dressing and feeding himself.

After he was released, Puyi got a job as a street cleaner and later a gardener at the Beijing Botanical Garden. He did ordinary things like riding the bus, doing radio exercises in the morning, and visiting a barbershop for the first time. He died in 1966. In the closing lines of his autobiography, written in 1960, Puyi states, “人 (rén, person) was the first character in my earliest textbook, the Three-Character Classics, but I never understood its meaning during the first half of my life. Thanks to the people of the Communist Party, to the re-education policy, I’ve understood the solemn meaning of this character and become a real person.”

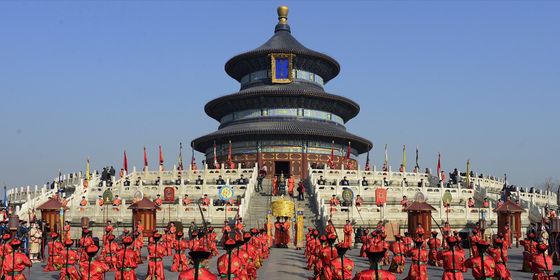

Cover image from VCG